50 Ways of Hearing "Marquee Moon"

In which I escape bleak reality by offering you a supercut of Tom Verlaine guitar solos.

Between reviewing for the Washington Post and catching up on end-of-the-year screenings for my Best of 2024 list, I’ve been deep into movies the past few weeks. Which means, somewhat perversely, that I’m going to write about music today, if only as a form of procrastination. But, fair warning, this one’s awfully niche-y.

So, yes, the election of two weeks past put a sizeable enough crater in my – well, my entire ontological understanding of life on Earth and the cursed human species as a whole – that I needed to just go away for a bit. I’m sure you understand. On the day after Election Depression Tuesday, I had a brief email back-and-forth with a food writer of some renown who I was surprised to learn subscribes to the Watch List, and we agreed that “Tonight we eat – Tomorrow we fight” was the only way forward.

For me, “eating” meant losing myself to a handful of cooking spirals – I currently have a ziggurat of Ina Garten pecan bars on my dining room table that are good mostly for yanking the fillings from the teeth of anyone foolish enough to eat one – and embarking on a home project of such magnificent pointlessness that it impressed even myself. To wit: Taking the guitar solos from 50 different bootleg versions of “Marquee Moon,” the proto-punk rock classic recorded by Tom Verlaine and/or his band Television over the course of 45 years into one monumental six-and-a-half-hour super-mix.

And here it is.

Who asked for this? No one, not a soul, not even me until the idea rose up in my brain sometime in late October like a bubble of swamp gas or a midnight visit from the Golem. It’s a profoundly, even exhilaratingly stupid idea, a slap in the face of what the late Verlaine accomplished, which was to conjure the demon spark of inspiration night after night and year after year while playing a song he surely grew sick of yet whose back half was a blank sonic canvas he never tired of filling with newfound colors and detail. In my post-election slough of despond, this seemed the numbing agent required – this assemblage of samizdat music, a treasure chest of sounds you weren’t supposed to hear unless you were there, into a security blanket of noise to sustain me until such time as we could figure out the new rules of resistance.

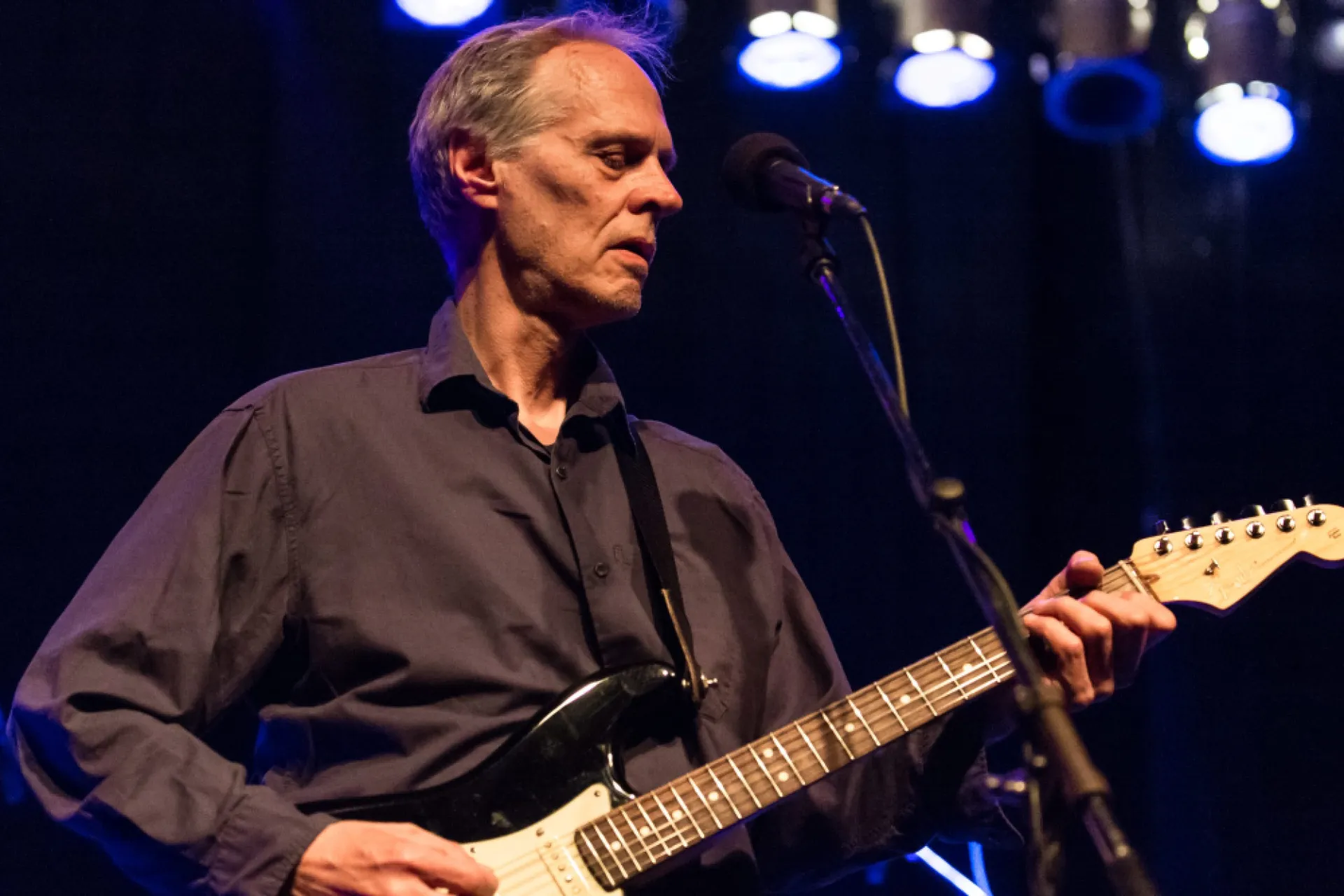

Some of you may be asking, if you’ve even made it this far, who the hell is/are Tom Verlaine and Television? Fair question, and one I wrote about at length after the singer-guitarist died of prostate cancer at 73 in January of 2023. (The New York Times obituary is solid, and there’s a marvelous piece at Literary Hub about the musician’s lifelong love affair with New York’s legendary Strand bookstore – in addition to being one of the greatest guitarists in rock history, Verlaine was an Extreme Bibliophile.)

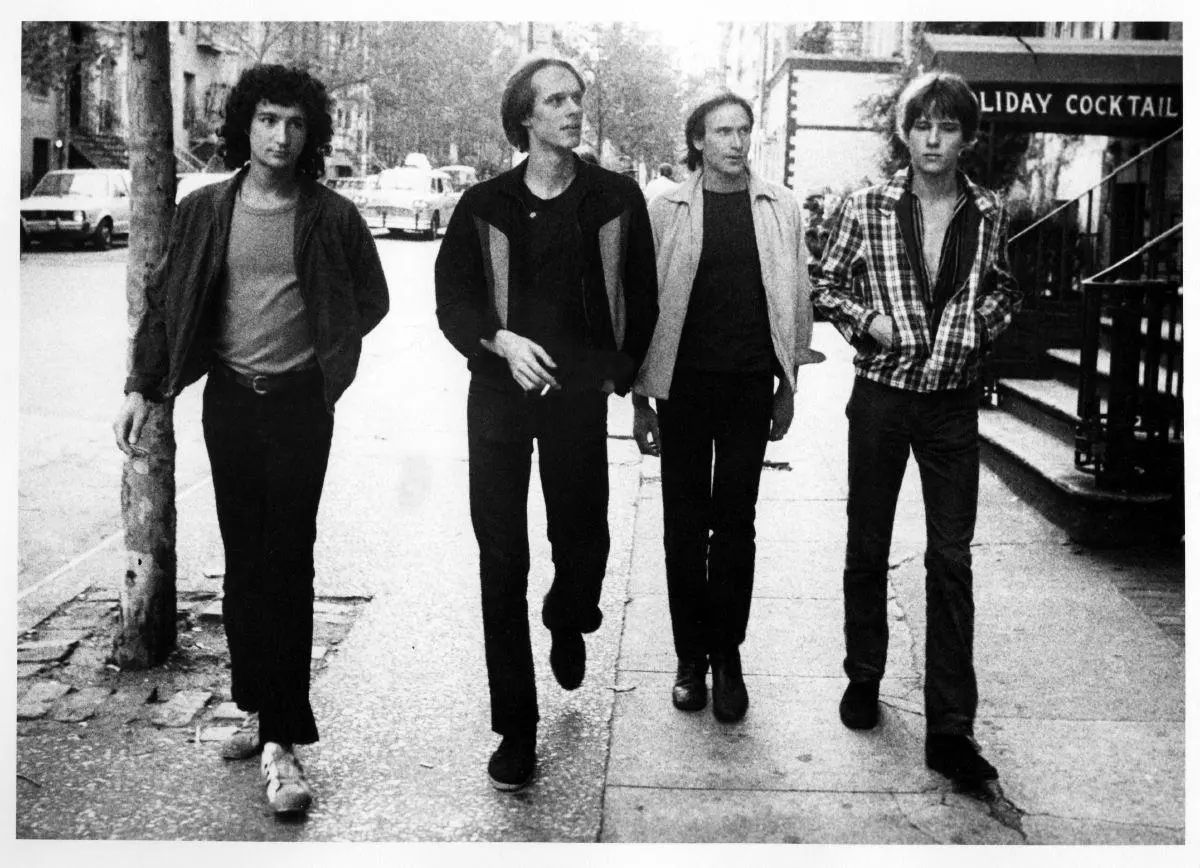

The quick history is that Verlaine arrived in New York as Tom Miller at the butt end of the 1960s and by the early 1970s was palling around with Richard Hell and sometime-girlfriend Patti Smith in the sounds and squall of whatever was happening on the Lower East Side. With second guitarist Richard Lloyd and drummer Billy Ficca, Hell and the rechristened Verlaine started Television, which is now encrusted in legend as the band that talked Hilly Crystal into letting rock groups play at CBGB (whose initials stood for Country, Blue Grass & Blues). The bands that followed them onto the stage at CB’s – The Ramones, The Dictators, Blondie, Talking Heads – defined New York punk and New Wave, but Television never fit into the short-sharp-shocked aesthetic, especially after Hell got bounced from the band and the much less aggro Fred Smith came in on bass.

Their songs were long, raucous, and mesmerizing, emphasizing the twin guitar interplay of Verlaine and Lloyd, whose runs circled around each other like WWI dogfighters. British fans often compared Television to the Grateful Dead, and that made a kind of sense; both were improvisatory jam bands founded on the electric guitar, both were best experienced in concert, both had healthy tape-trading subcultures. But where the Dead espoused mellowness, Television was angular and rough-edged and hermetic, a dark New York alley instead of a sunny Marin County meadow. Verlaine’s musical influences ran the gamut from Stravinsky and Albert Ayler to garage-rock nuggets like “Psychotic Reaction,” and in concert, where the band came alive, he explored more corners of the sonic universe than you knew existed. The signature tune “Marquee Moon” was both the centerpiece and the climax of the live shows, and if it ran an un-punkish ten minutes on the band’s 1977 debut album, in concert it could surge past the 20-minute mark and head toward the exosphere.

The official recorded canon – three studio albums (1977, 1978, 1992) and three live releases – is but the tip of an immense unheard iceberg. Verlaine’s finest work as a guitarist is contained on dozens of bootleg tapes, most of them sounding like crap but still approaching the very heavens when Verlaine or Lloyd let loose. I personally own copies of about 45 of them, collected via various sources over the decades. Because 99% of the people who’ve ever heard “Marquee Moon” have only listened to the studio version, this live legacy is one of the great secrets of rock history, which is one reason I found myself drawn to this most insane of tasks, stitching together Verlaine’s solos into one sprawling, obsessive sonic journey.

Here's how it works. You’ll hear the first half of the song only in the very first cut, the demo that Television cut with Brian Eno in 1974 in hopes of a record deal that never materialized. After that, I crossfade straight to the solos of the ensuing tracks in chronological order, from 1975 to 2019. Midway through any version of “Marquee Moon,” after three verses of caterwauled lyrics, the band takes a pause, and Richard Lloyd restarts the riff that serves as both the song’s pulse and the blank canvas that Verlaine proceeds to work atop. His solo will explore various planets of known sound for any number of minutes, and then the band will come back in for a stairway-to-heaven build to a climax, at which point the song will end – sometimes. By the 1980s, after Television had temporarily broken up and Verlaine was playing “Marquee Moon” in concert with his own band, the guitarist would often keep going after the applause had died down, atomizing the notes, reverse-engineering the chords, and scratching the fretboard in search of something new, something new, something new. On good nights, he achieved it – the holy grail of rock transcendence. On other nights, maybe not, and maybe it didn’t matter. Tom Verlaine was one of the great musical seekers, and the search was the point.

A caveat: I am not an audio technician, and the sound levels on the various tracks have not been balanced because I don't know how to do that with any degree of proficiency. Some of the crossfades are ugly. Also, the early tracks are pretty skronky, so you may or may not want to drop in at the 17:45 mark: The second night at the Piccadilly in Cleveland, 1976, with decent sound and a solo that’s close to jazz. Or the 1976 CBs show at 29:53. Or, no, this one: a monumental stand at Boston's Paradise club in 1982 that ends with four minutes of musical Cubism. Or start at 3:37:24, a 1987 New York concert I recorded myself and that I've come to love as a personal talisman. I recommend earphones or headphones. The damn thing is six and a half hours long, and I’ve listened to it twice, often in the background or while out for a walk but also sometimes wallowing in the pure sensuality of his sound – how Tom could make an electric guitar sound unbearably tender or thrillingly savage in ways no one else has ever quite matched.

And how about this? – the theory I wanted to test turned out to be true. In 45 years of playing this song, in hundreds of venues and dozens of towns, Tom Verlaine never repeated an idea. Not once. You might hear the same notes, but played with radically different energy and attitude, or a riff would transform from concert to concert like a living thing, or sometimes he would reinvent the whole damn song or concept of what a solo even meant from the ground up. It was as though every time he played "Marquee Moon" he was finding a new old book on the outdoor stands at the Strand, riffling its pages and lighting a smoke and wondering what endless worlds it could possibly contain.

Thanks for indulging this side journey from my usual cinematic postings. I'll be sending out this week's Washington Post reviews ("Wicked," ⭐ ⭐ ⭐ 1/2; "Gladiator II," ⭐ 1/2) to paid subscribers in a bit. Feel free to comment, as always.

Or sign up for a paid subscription so you can comment, as well as get extra content. Thanks in advance.