"A Hero" arrives, an icon returns

A new Asghar Farhjadi film on Amazon Prime, a new Buster Keaton biography in bookstores -- it's a good week.

The Nut Graf1: “A Hero” (on Amazon Prime Video, ***1/2 stars out of ****) is another gripping moral tale from Iranian Oscar winner Asghar Farhadi (“A Separation”). A fine new Buster Keaton biography takes in the century in which he lived.

On its surface, “No good deed goes unpunished” would seem to be the moral of “A Hero,” a 2021 Cannes prizewinner and the latest scrupulously observed social drama from two-time Oscar winner Asghar Farhadi (“A Separation” in 2011, “The Salesman” in 2016). The longer we watch, though, the more compromised and qualified – the more human – the film’s central character becomes. Is a selfless act tainted by having a selfish motive? Is the only real heroism that which nobody sees? The movie embeds these conundrums in a caustic and suspenseful story of a decent man driven to desperate measures, and it widens to enfold the society that surrounds him.

“A Hero” arrives on Amazon Prime Video today after a limited theatrical run to qualify for the 2021 Academy Awards, for which it will almost certainly be nominated in the foreign-language category. Farhadi deposits us not among the bourgeoisie or in the theatrical circles of earlier movies but in the working class of the Iranian city of Shiraz. A sign painter and calligrapher named Rahim (an immensely appealing Amir Jadidi) is out on a two-day furlough from debtor’s prison, eager to make things right with the stone-faced brother-in-law (Mohsen Tanabandeh) from whom he borrowed money when his business went under. Finding a bag with a small fortune in gold coins on the street, Rahim and his girlfriend, Farkhondeh (Sahar Goldoust), dither whether to use it to pay off the debt, but conscience wins out. In returning the money to its rightful owner, Rahim becomes a media sensation: The last honest man. As a result, a local charity raises money to repay the brother-in-law and the prison warden arranges for a government job. Everything is going Rahim’s way. And then it doesn’t.

It’s a tribute to Farhadi’s skill as a storyteller that we have doubts about Rahim and his tale from the start, uncertainties that are amplified as rumors proliferate in the street and on social media. “A Hero” leaves gaps in the narrative into which we pour our suspicions, some warranted and others not. Why does Rahim say he found the bag when Farkhondeh did? Why did anyone wanting to claim the bag have to call him at the prison – and thus alert the warden to his good deed – rather than on his cellphone? How much of his altruism is staged, if any?

In addition, “A Hero” surrounds its hero with a scrum of family members, neighbors, and rubberneckers: A matronly older sister (Maryam Shahdie) and her stalwart husband (Ali Reza Jahandideh); Rahim’s stressed-out young son, Siavash (Saleh Karimaei), burdened with a heavy speech impediment; the daughter (Sarina Farhadi) of the man who lent Rahim the money, seething at a dowry that has disappeared; a Kafkaesque potential employer (Ehsan Goodarzi), blandly insisting on proofs that lead to more hedging, more subterfuges, a deeper hole to dig oneself out of. The miracle of Farhadi’s cinema is that every face is its own movie, and we’re encouraged to script it for ourselves. The canvas keeps expanding to take in a city and a country of goodhearted but paranoid busybodies who want to think the best of others but use any excuse to believe the worst. This may just be how life is in a bureaucracy backed by a theocracy, but the movie’s lessons apply just as well to where you and I live.

Farhadi works in a key of wide-screen realism, the better to let everyone have their say. A sequence in which Rahim and Siavash search high and low for the woman who claimed the bag – she may or may not have been a con artist – is reminiscent of the classic “Bicycle Thieves” in its portrait of a fraying father and his trusting son. Just as that film’s title pointed in two directions at once, so heroism in “A Hero” comes to mean different things, one of which is celebrated by a fickle society and the other of which leaves a man with nothing but the knowledge that he did the right thing. By the haunting closing scenes of “A Hero,” we finally come to trust Rahim by watching him come to trust himself.

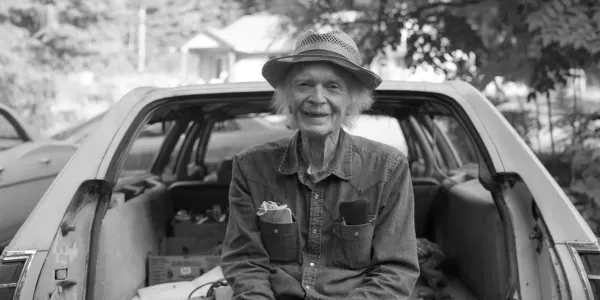

Why do we need a Buster Keaton biography in 2022? The title of Dana Stevens’ splendid, thoughtful “Camera Man: Buster Keaton, the Dawn of Cinema, and the Invention of the Twentieth Century” (Atria Books) serves as its own answer. (Caveat: Stevens is a fellow movie critic — she writes for Slate — and a friend.) Any appreciation of Keaton tends toward the philosophical, but Stevens’ book makes clear that we’ve had to get beyond the 20th century to understand how truly the comedian embodied it. He’s what we would now call the era’s avatar: a small but precise image of an unsmiling man amidst chaos. The two writers most responsible for Keaton’s artistic rehabilitation in the latter half of the 1900s reached for similar metaphors to describe the wheel of the world and Buster at the center of it:

In a way his pictures are like a transcendent juggling act in which it seems that the whole universe is in exquisite flying motion and the one point of repose is the juggler’s effortless, uninterested face. – James Agee, Life magazine, 1949

Though there is a hurricane eternally raging about him, and though he is often fully caught up in it, Keaton’s constant drift is toward the quiet at the hurricane’s eye. – Walter Kerr, “The Silent Clowns,” 1975

For me – and for a lot of people, including, I think, Stevens – it’s Buster in long shot that can be most moving, even as you’re laughing at the absurdity of the situations or gasping at the grace of his stunts. That tiny figure seems almost lost in a field of overwhelming forces (windstorms, boulders, armies, cops) yet either remains solemnly upright against the tide or races just ahead of the tsunami. It was Chaplin who got caught in the factory gears in “Modern Times,” but it was Keaton who pulled the camera back to remind us that being caught in the gears might be the human condition. That he chose to make the image comic rather than tragic is what gives it gravity – that and the beauty of his deadpan. We laugh at Keaton not until our sides ache but because our sides ache.

Beyond being a deeply researched and fully felt telling of Keaton’s life and career, from his child stardom as a human bowling ball in his family’s vaudeville act through his vital and busy final years, “Camera Man” has two things going for it, one inside its pages and the other external to them. The first is right there in the subtitle: How a consideration of Buster leads by necessity to a reconsideration of the 20th century. Again and again, “Camera Man” takes detours into social history, as though Stevens had turned off her biographer’s GPS and followed the back roads of social history by dead reckoning. We learn about: Child welfare societies and the shifting meaning of childhood; the long-forgotten Childs restaurant franchise; the rise and fall of Mabel Normand and Hollywood’s banishing of women directors as the great studios took shape; the anarchist movement; the birth of build-it-yourself kit homes; critic/playwright/screenwriter Robert Sherwood (an early Keaton enthusiast); blackface and Bert Williams; F. Scott Fitzgerald; the founding of Alcoholics Anonymous and changing understandings of alcoholism; the coming of television and its uses for an aging sketch comedian. It’s the widest of wide angles: Buster, tiny and stoic, at the center of a landscape that expands past the horizons.

There have been a number of canonical Keaton biographies: Rudi Blesh in 1967, Tom Dardis in 1979, Imogen Sara Smith in 2008. Stevens’ is one of the few to paint the comedian’s later life as more than decades of drunken wallowing followed by a final sprint of redemption. (It was the other way around: The worst years were the early 1930s, and, barring a couple of relapses, Keaton was sober and creatively engaged from 1935 to his death in 1966.) She may be the only one to examine the comedian within the larger social framework of his times.

The other great asset of reading a Buster Keaton biography in 2022 is that you can watch everything Stevens is writing about. The compleat Keaton, from his apprentice shorts with Fatty Arbuckle through the great features of the 1920s to his Where’s Waldo-like TV appearances in the 1950s – it’s all available on YouTube. (The book’s passages on the short comedies that Arbuckle made with Mabel Normand make you want to see them straightaway, and, guess what, you can.) Compare this to 1949, when James Agee was extolling Keaton in the pages of Life and there was nowhere outside a studio vault where you could see the films. In the 21st century, Buster Keaton has become what he only played at being in the great dream sequence of 1924’s “Sherlock, Jr.” He’s the ghost in our machine.

If you enjoyed this edition of Ty Burr’s Watch List, please feel free to share it with friends.

If you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to sign up for additional postings and to join the discussions, here’s how:

If you’re already a paying subscriber, I thank you for your generous support.