Father, Christmas

Some notes on the prism of holiday memories.

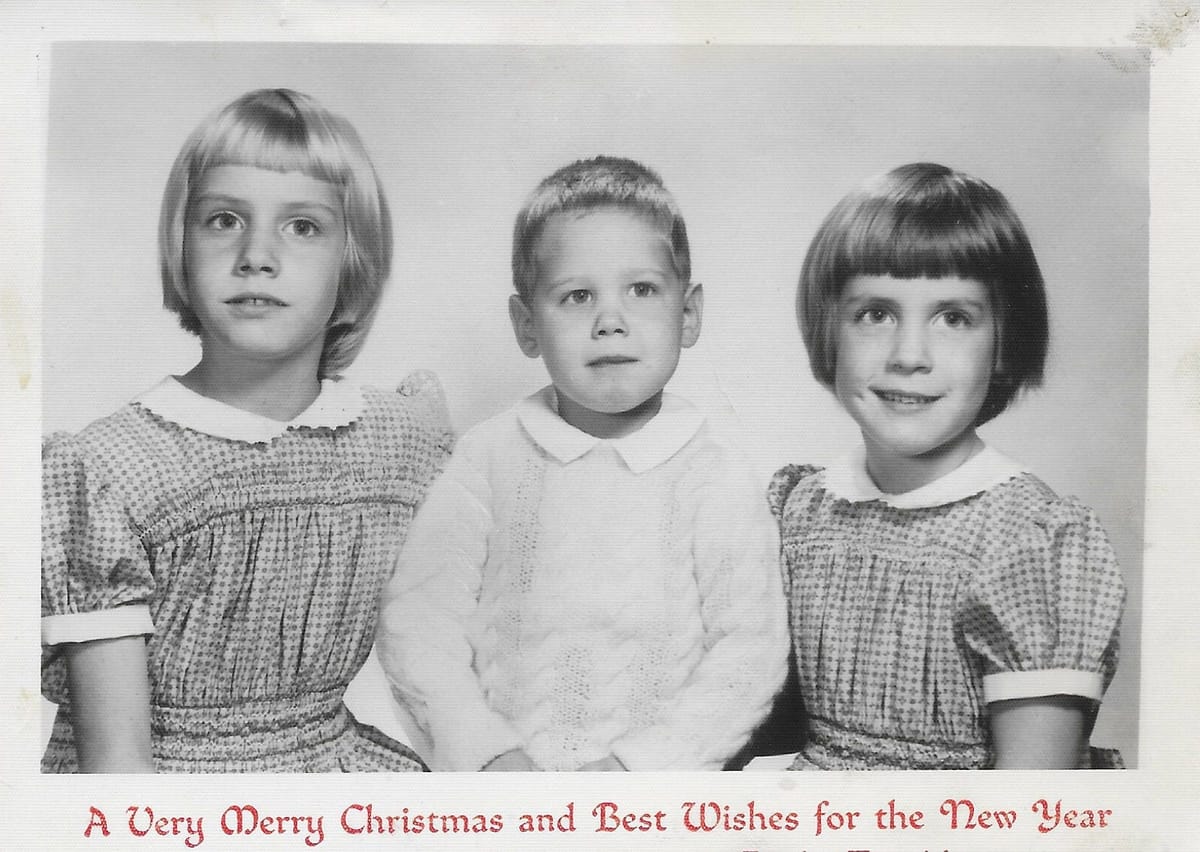

The December holidays are a time when all one’s family members return home – the living and the ghosts. It can get rough. I’m sixty-five years old and this morning I felt freshly haunted by my father, who died when I was nine and whom I never really knew. I’ve written of him before – this is one way of conversing with a ghost – and of the warmth and gregariousness he shared with his peers and, at a distance, with his three children, whom he figured he would get to know better when they had grown up a little. Funny how that works out.

I had ten Christmases with him, only two or three of which are in memory: Two or three Christmas mornings of my older sisters and me waiting antsy in pajamas while he finished his coffee and morning cigarette, stretching the moment out with mischievous eternity, then looking at my mother and the two of them nodding to each other – it’s time – and three children blurring like rockets down the hall from the kitchen to the living room, to the stockings and the tree and the loot. We were blessed; upper middle-class, free from want, free from sorrow. A bubble of privilege, which, if you’re lucky or cursed or both, bursts sooner rather than later.

My memories of him are frustratingly few – why wasn’t I paying more attention? what did I miss? – and in place of memories my sisters and I tell stories. Some families put out cookies and milk for Santa Claus; at least once we put out a cigar and a double martini on the rocks with a twist of lemon. In the morning, the martini glass was empty, the cigar smoked two-thirds down. Presumably Santa wasn’t pulled over for a DUI. Years later, we learned from my mother that my father drank the martini and she smoked the cigar.

Another holiday memory, this one from my mother. There was one Christmas night, after we kids had gone to bed, that involved a ridiculous amount of assemblage: A bicycle for my older sister, a rocking horse for my middle sister, a kiddie car for me. My mother sat on the living room floor, surrounded by manuals, wrenches, and T-bolts, waiting for my father to come home from his office Christmas party and help out. He rolled in at a late hour, having driven a few co-workers home and stopped for a drink at each house; within five minutes, he was asleep on the couch. My mother angrily finished putting all the toys together, wrenching the lug nuts so thoroughly that she wrenched her elbow. She spent Christmas morning in an improvised sling. That I remember.

She always told the story with a laugh and a shake of her head, and we laughed for a while too, hungry for any glimpse into this person who left us too soon. Family anecdotes always tell you more than you may be willing to hear: I know of one clan whose tales of a hilarious grandfather suggest to an outsider a bully, one whose marks you could see in his sons – in the very stories they told to turn pain into veneration. You build your house from the timbers you’re handed.

In my Christmas morning memories, my father stands in his bathrobe by the fire, working on his third cup of coffee and smoking the cigarettes that would kill him in a few years, reveling in our joy as we rip open our consumerist bounty. It’s a Polaroid snapshot of frozen warmth, which if he’d lived even a little longer would have had more nuanced gradations of color and light and shade. It’s an odd fact that anybody who has lost a parent when they were young calls him or her by the name they were left with, no matter how old they become. So for my oldest sister, my father is often “dad,” while my middle sister and I are still stuck on “daddy.” It’s a childish habit that, at 65, I suddenly feel ready to break, maybe because by now I’ve built up enough Christmas morning memories of my own, sipping coffee while watching my children open their own gifts, their presence in my continued presence a gift my father and I were never able to share with each other.

Merry Christmas, Dad. Merry Christmas, Mom, and Merry Christmas, dear sisters. Merry Christmas and happy holidays to my wonderful wife and my two astonishing, now grown kids. And happiest of holidays to you, dear readers. May you be lucky enough to embrace your family in all its loving, fractious, complicated entirety. And may you raise a toast to the ghosts in your own life and invite them to come sit at the table.

You are welcome (and encouraged) to share your own holiday memories in the comments.

Also, thanks for reading. I usually write about movies and popular culture but occasionally about other things that move me, as is the case here. You can pass this along if you’d like.