Kvell Is Other People

On "Shiva Baby" and the humor of chagrin

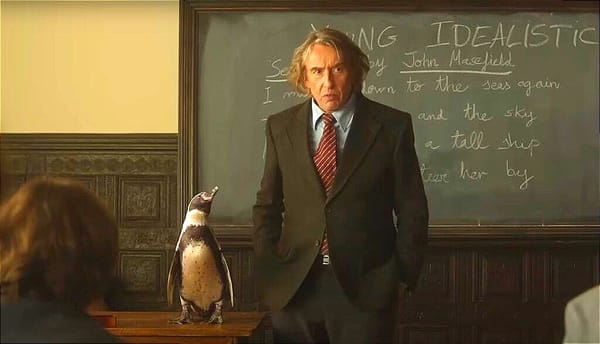

The comedy of Jewish American mortification is almost exclusively male. Its literary roots are in Kafka – who hasn’t woken up some mornings feeling like a giant bug? – and its patron saint (you should pardon the expression) is Philip Roth, for whom Portnoy and his literary brothers were self-loathing, self-aggrandizing templates for a generation of boy-men desperate to escape the Tribe into America. Those boy-men are many, and they include the hero played by Charles Grodin in Elaine May’s “The Heartbreak Kid” (1972), dumping his wife on their honeymoon to chase shiksa Cybill Shepard (say that three times fast and you might become a goy); the beleaguered, infantilized son played by George Segal in Carl Reiner’s “Where’s Poppa?” (1970), whose mother (Ruth Gordon) only wants to give him a kiss on the tuchus; the pompous professor played by Michael Stuhlbarg in the Coen’s “A Serious Man” (2009), with his son stoned at the bar mitzvah and the Apocalypse at the door.

By contrast, the women of the genre are generally portrayed as castrators and temptresses and millstones, and very rarely are these stories their own. That’s what makes “Shiva Baby” revolutionary in its micro-indie way, because the comic embarrassment of Emma Seligman’s movie – the social disasters small and large, the desire to flee one’s birth culture like an edamame popping from its skin – is experienced by a young woman, Danielle (actor-comedian Rachel Sennott), as she tries to hold it together during the shiva from Hell.

Danielle is in her early twenties and floundering. When we first see her, she’s out of focus in the background, having sex with someone while her phone, razor-sharp in the foreground, buzzes with a call from her mother. Is Danielle coming to the shiva this afternoon? Of course she is. Wait, mom – who died?

It becomes clear that Danielle and the man, Max (Danny Defarrari), have a transactional relationship: He’s her sugar daddy, paying her for sex. The arrangement gives Danielle needed cash and the illusion that she’s in control of her life and, anyway, Max seems like a mensch. A shiva, for those who don’t know, is a seven-day period of mourning during which the family of the deceased stays home and receives visitors; it’s not a wake but in secular, suburbanized American Judaism it fulfills a similar function. For a young adult, it’s the kind of social occasion where friends of your parents who haven’t seen you in years want to hear the good news and only the good news. Are you in graduate school? Have you met a fella? Do you have a job? Do you have direction?

For Danielle, it’s none of the above, and Sennott deftly registers outward politeness and inner terror as her character responds to all the kvelling with generalizations and lies. It’s pretty bad, and then it gets worse. First, Maya (Molly Gordon) shows up; she and Danielle had a thing in high school and caused a scandal by going to the prom together, and now Maya is everything Danielle is not. (For one thing, Maya is going to law school. Such naches.)

And then Max shows up, with a wife Danielle didn’t know he had – Kim (Dianna Agron), a sleek blonde entrepreneur – and a remarkably unpleasant toddler. Danielle’s mother, Debbie (Polly Draper), noodges her daughter to go talk to Kim, for goodness sakes, make some connections. You can practically hear the gears in the poor girl’s head grind to a halt.

“Shiva Baby” is all of 77 minutes long, but from the heroine’s perspective it goes on for days. The disasters and humiliations are small but Biblical in number: Spilled coffee on a white shirt, a missing iPhone with incriminating texts, a sideboard nail that tears a stocking and causes a scratch that won’t stop bleeding. Seligman keeps the camera jittery and the soundtrack music off-kilter; the whole thing feels itchy, and if you’re prone to panic attacks, this is not the movie for you.

So why is it here? Because it’s awfully funny in its worst-case-scenario way, and because all the tsuris pays off in an unexpectedly moving scene late in the film. Despite everything Danielle thinks she doesn’t deserve, there is resolution. And because the performances are delightful, dancing on the line separating cultural caricature from observational empathy. Draper is especially good as a loving busybody of a mom who only sees what she wants her daughter to be (which is happy) and not what her daughter is (which is miserable and stuck). The background is filled with character actors like the invaluable Jackie Hoffman, with her cat-eye glasses and a voice like a gravel road. Danielle’s father is played by – has to be played by – Fred Melamed, who looks like a blobbier version of Richard Deacon on the old “Dick Van Dyke Show” or a character from a Dave Berg strip in a vintage copy of “Mad.”

These actors are physical types as well as skilled professionals, and that makes some people uncomfortable. When I reviewed “Shiva Baby” for the Boston Globe, a commenter complained that the movie was anti-Semitic; the Coens fielded similar accusations with “A Serious Man” (which also featured Melamed). In both cases, I strenuously disagree. As in Roth, the comedy and the meaning of these movies are rooted in the deepest, most lived-in familiarity, their exaggerations formed from a double helix of rebellion and love. The Coen brothers based their movie on their own father. Roth carried Newark within him for life. In “Shiva Baby,” Emma Seligman welcomes a prodigal daughter home with fondness, clarity, and rugelach.

“Shiva Baby” is available for streaming on HBO and HBO Max and for rental on Google Play, YouTube, Apple TV, and Fandango Now.

If you enjoyed this edition of Ty Burr’s Watch List, please feel free to share it with friends.

Or subscribe. Thank you!