Michael Hurley 1941-2025

The original freak-folkie and one of this country's great outsider artists has passed on to the jamboree in the sky. You don't know what we've lost.

Note: A reminder for any readers in the Boston area that I'll be screening and discussing "A Serious Man" (2009, ⭐ ⭐ ⭐ ⭐), the Coen brothers' greatest film (you heard me, and no arguments) tonight at 6:30 at the West Newton Cinema. Advance tickets are still available or you can buy 'em at the door; proceeds go to the cinema's renovation fund. Please feel free to come and bat around the concepts of Judaic assimilation, quantum theory, the Jefferson Airplane and Schrödinger's Cat.

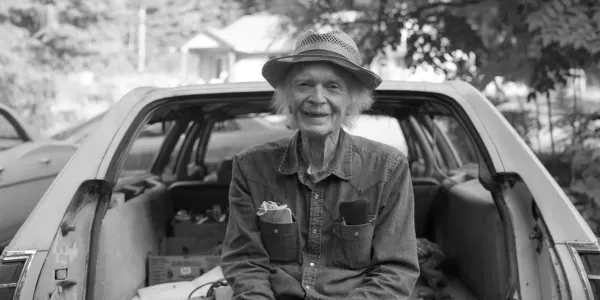

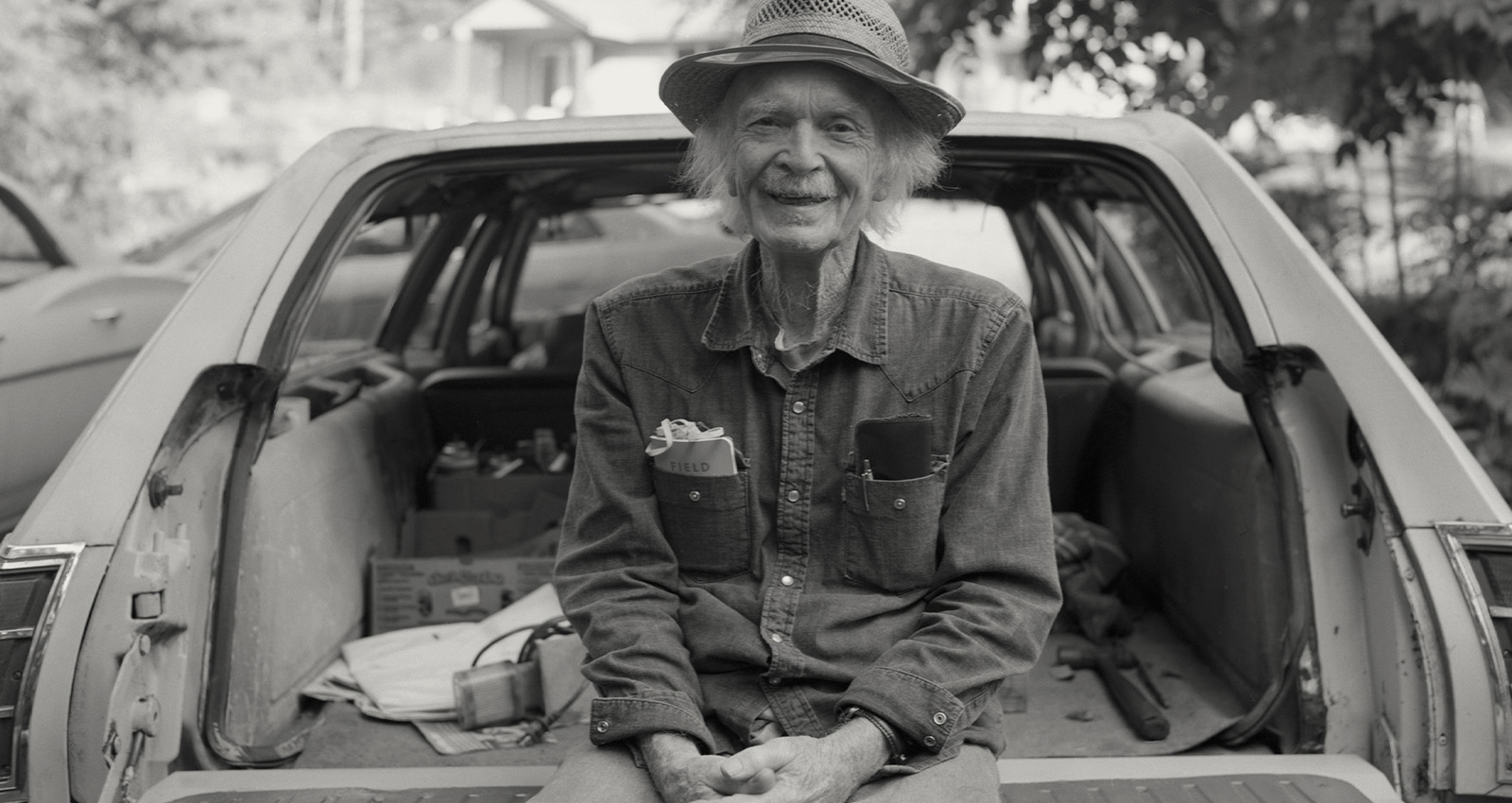

Michael Hurley has passed away at the fully ripened age of 83, but in truth, I thought he'd be around forever, a wily old birch tree too knotty and ornery to be cut down with the rest of the timber. He existed on the fringes of the folk/acoustic/outsider music scene for most of his life, recording when he felt like it (or had kids to feed) and touring when the mood struck him (or he had kids to feed). I count myself lucky to have seen him live twice in his waning years, when he'd sift from among the hundreds of songs he'd written that lived in his head, along with the characters that populated those songs: Werewolves and wolverines, monkeys on the interstate and Martians from Mars, sweet Lucy and the dishes over there that filled him with despair.

Every so often, Hurley would pop up into the mainstream, as in the early years of this century, when a new generation of freak-folkies like Devendra Banhart and Cat Power discovered him. He had a song on the "Deadwood" soundtrack and there he was singing around a campfire in Debra Granik's 2018 father-daughter drama "Leave No Trace." But he carved his own way through life and a career with the kind of individuality that marks the great American eccentrics, the ones who know exactly what they're doing and don't mind if you tag along.

A 2015 Boston Globe feature I wrote about Hurley is appended below; talking to him was, as you will see, a trip of the highest order and a memory to be savored. I also have a Spotify Hurley playlist that I've returned to over the years and that has been getting a lot of play this past week. I hope you enjoy it, and I hope you come to appreciate this strange and precious man, one of those artists that somehow falls between the cracks of this country while simultaneously shoring it up. He will be missed even by those who never heard him.

The long, strange trip of folk artist Michael Hurley

(Originally published in the Boston Globe April 9, 2015)

There aren’t very many American originals left. Michael Hurley is one of them.

You probably haven’t heard of Hurley, but it’s not like he hasn’t been out there for more than 50 years, playing his odd, eternal strain of folk music and recording when he gets a mind to. Although he currently lives in Astoria, Ore., he put in a lot of time in the Boston area back in the day, and he’s swinging by the Somerville Armory Wednesday for an extremely rare gig. Attention must be paid, if only because you may not get a second chance.

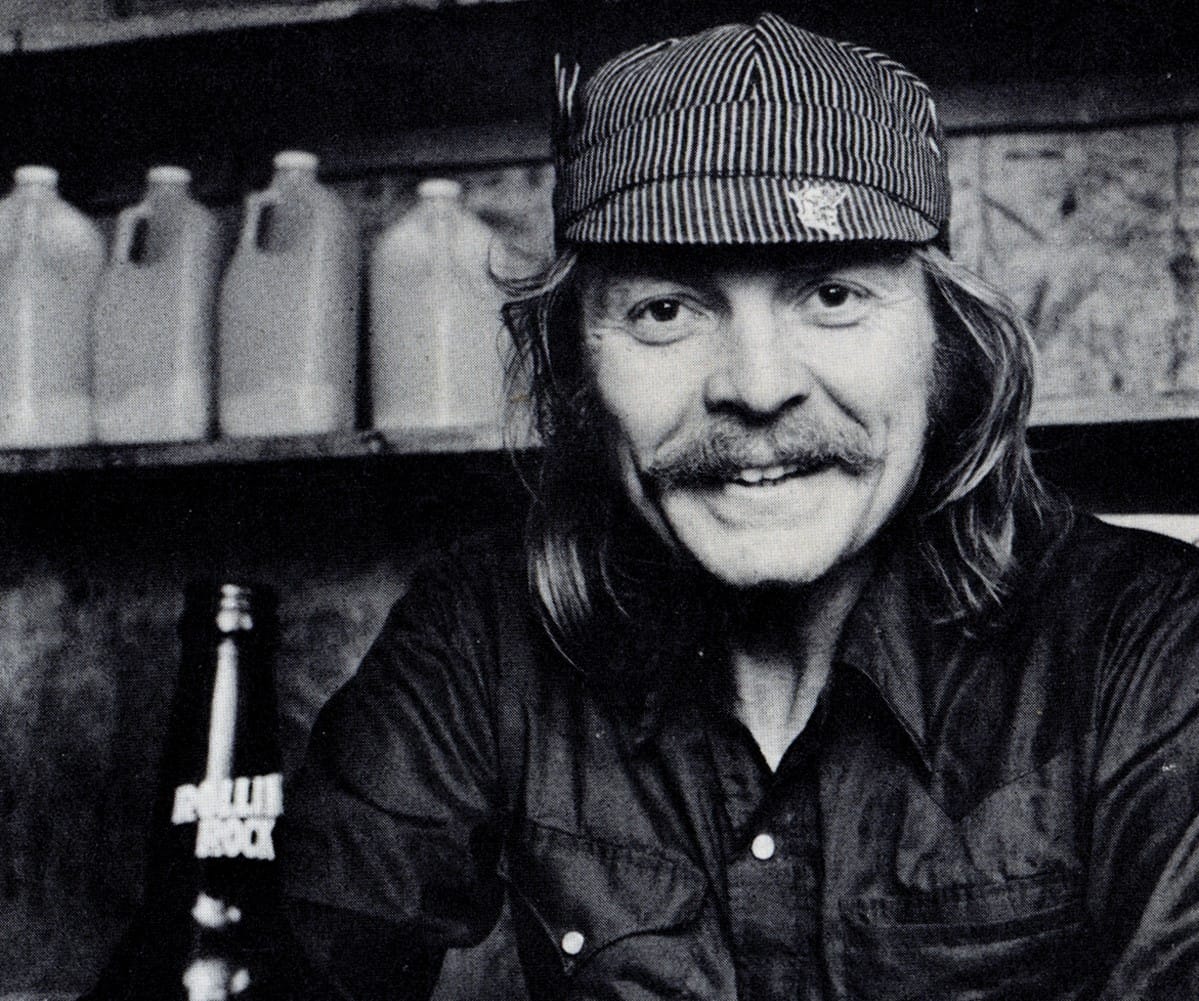

Now 74, Hurley’s one of the last survivors of the Greenwich Village folk boom of the early 1960s. He’s more than that, though — more deeply rooted. With his cracked voice, skewed comic vision, and a ragtag musical sensibility that seems to span centuries, Hurley’s a vestige of the “old, weird America.” That’s the phrase that critic Greil Marcus used to describe the universe of folk, blues, country, gospel, and mountain music that Bob Dylan and all the other hairy young rebels of the counterculture tapped into in an effort to find common ground. Hurley is part of that response, for sure, but he’s part of an earlier, more primal urge, too.

His music, performed solo on acoustic guitar or with small bands of like-minded individuals, can be crazy funny at times. Alternately, it can haunt a listener beyond words. Hurley’s most well-known tune may be “Werewolf,” which he has recorded three times over the years and which is sung from the point of view of a sociopathic supernatural creature that roams the night. It may be the loneliest song I’ve ever heard.

“Werewolf” is an outlier compared to Hurley’s usual fare, which mines a unique vein of American surrealism. His songs are full of talking pork chops, monkeys on the interstate, fractious little Martians, and demonic swine. The last is from “Hog of the Forsaken,” a stand-out on the soundtrack to HBO’s “Deadwood” a while back. On occasion, the mainstream has seen fit to embrace this strange, original man.

In fact, Hurley’s career got a boost about 10 years ago, when he was discovered by a new generation of lo-fi misfits. Cat Power covered “Werewolf” on 2003’s “You Are Free,” and alt-folkie Devendra Banhart released a 2007 Hurley album on his Gnomonsong label. Hurley has toured with the likes of Lucinda Williams and Son Volt. He could be, you know, big.

He’s bigger than that, though, in part because he’s so comfortably small. It’s in his aw-hell rustic minimalism that Hurley is precious; the world is his front porch. When I called him up earlier this week for a chat, it was like conversing with an acoustic Zen Yoda, his half of the conversation coming after long pauses, as through streaming across the galaxy from Planet Hurley.

I asked him about “snock,” which is a recurrent word and vague philosophical concept in his album titles and songs. I’d always thought it had something in common with “slack,” a sort of live-and-let-live pothead mellowness. Turns out it’s just his nickname, born of a vision he had in his youth of a symphony of claves and other percussion instruments clacking away. “I said, well, this is me,” Hurley recalls. “It was a kind of a hallucination. An auditory one.” Pharmaceuticals may have been involved.

He originally came out of Bucks County, Penn., with an interest in old-timey music, a way with a guitar, and not much of a work ethic. After recording a 1965 solo album on Folkways — a long-time rarity, it was re-released on CD as “First Songs” in 2010 — Hurley neglected to follow it up with a tour. Basically, he just forgot. “It never occurred to me that I should go out and start pumping it,” he says. He went to Mexico instead, and, when he returned, discovered he’d been booked into a folk festival at Carnegie Hall. That was his first real gig.

He let the momentum slip, though, and wandered up to Harvard Square. In six or so years in the Greater Boston area, Hurley held down a series of odd jobs: punching out venetian blinds in a factory, putting cookie dough on a conveyor belt, working as a janitor at the old Paris Cinema. What he didn’t do was perform. “I was married and ended up having three children,” he says, “so that keeps you on the stick. You gotta make hay.”

But an old friend named Perry Miller had changed his name to Jesse Colin Young, formed a band called the Youngbloods, and had a 1969 Top 10 hit with “Get Together.” (“Come on people now, smile on your brother” — that one.) Young found himself with his own label, Raccoon Records, and put out Hurley’s next two albums, “Armchair Boogie” (1971) and “Hi Fi Snock Uptown” (1972).

“I said, well, if he’s going to do this, I might as well get out and get in front of some of these clubs,” Hurley says. “It was the advent of the hippie bar. There were two of them, one of them was in Somerville — maybe both of them were. I forget the names. One of them was The Apple, I think. Before that, there were no hippie bars. I didn’t like bars much, because I was a hippie.” Meaning you could get beaten up? “If you had a few drinks, maybe, and you got mouthy, like I tend to do.”

Hurley took part in “Have Moicy!,” a legendary 1976 meeting of damaged minds with the Unholy Modal Rounders and Jeffrey Frederick and the Clamtones that longhairs used for years to delight and terrify their children.

And then it was off to four decades of wandering in the unplugged wilderness, pausing every so often to record. A newcomer might want to start with 1984’s “Blue Navigator,” which includes a spectral version of “Werewolf”; only 1,000 copies were pressed and the master was later destroyed in a studio fire, but you can get it from Amazon in an MP3 version copied from a vinyl survivor. Somehow the pops and hiss make it sound better.

Other recommended starting points are “Long Journey” (1976), “Watertower” (1988), or “Ida Con Snock” (2009), which contains the hair-raisingly beautiful “Wildegeeses.” But there’s no such thing as a bad Michael Hurley record. In concert, he performs without a set list, pulling from the hundreds of tunes collected in the songbook of his mind.

Like your grandpa, Hurley collects and futzes around with antique radios. Unlike your grandpa, probably, he has a 5-year-old daughter. That’s partly why he’s touring without a new album to promote, although one is in the works. “I have to work more now,” Hurley laughs. “At least I can work with music. Something I love.”

Because his records come out on small labels and because he draws his own album covers, Hurley has been dubbed an outsider artist by some. But that’s not quite right; he’s pretty ambitious for an old hippie. But neither is he a music business insider. He occupies the gray zone between those ancient Harry Smith field recordings and the acoustic revisionism of youngsters like Banhart and Bon Iver. Hurley, in fact, may be what Bob Dylan always wanted to be when he was pretending he was an itinerant troubadour.

He’s the last folk artist. He is pure.

Feel free to leave a comment or add to someone else's.

Please forward this to friends! And if you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to sign up for additional postings and to join the discussions — or just help underwrite this enterprise, for which the author would be very grateful — here’s how.