My Favorite Martians

On "Good Night Oppy" and the human faces of science

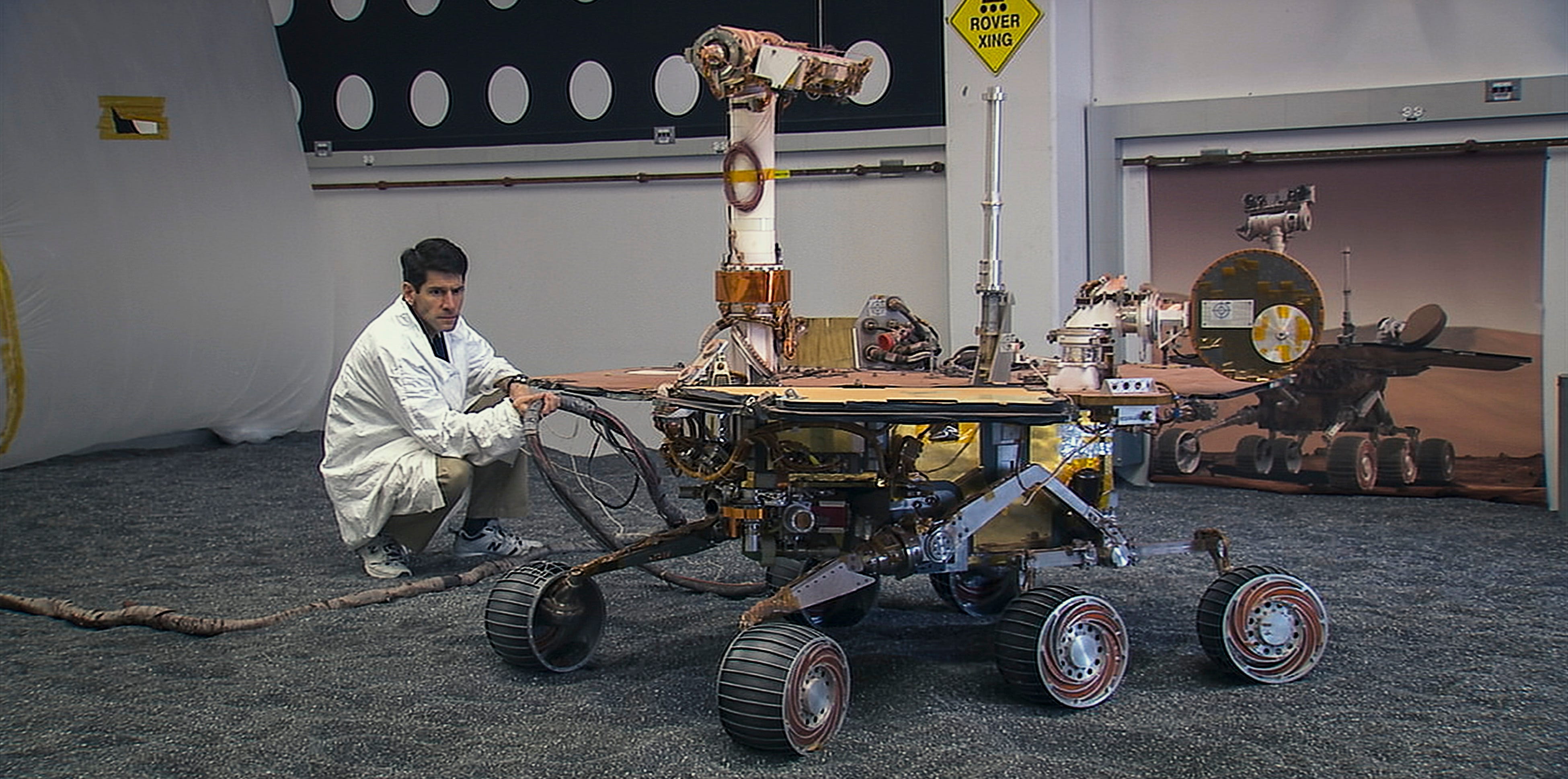

Who knew that a documentary about a robot could leave you verklempt? The inspiring drama that propels “Good Night Oppy” (⭐ ⭐ ⭐, now streaming on Amazon Prime) is the narrative of how NASA scientists put a pair of mobile data collectors dubbed Spirit and Opportunity on the surface of Mars, where they were meant to go about their tasks and expire after three months. Instead, they kept going and going and going, with Opportunity tooling around the Red Planet until 2019, a full fifteen years past its shelf date.

The film’s emotional storyline, though, is something else entirely – a testament to the ways humans are drawn to anthropomorphize and even sentimentalize their work. You won’t find a more dedicated group of STEM diehards than the crew of rocket scientists and mechanical engineers headed up by Steve Squyres at the space agency’s Jet Propulsion Lab in Pasadena, CA. Numbers wonks to a man and woman, they nevertheless describe the two Mars Rovers to director Ryan White as “children,” “friends,” “family members.” “Spirit was troublesome [but] Opportunity was Little Miss Perfect,” one of the robotics engineers says about two machines that were built to be identical twins. “It’s just a box of wires, right?” says someone else, and he doesn’t sound at all convinced. Were the robots built at a human height and with cameras spaced to mimic human eyes so they would “see” from a human perspective – or just because we need to make things in our own images? The movie raises the question but is too dazzled by wonder to answer it.

And there’s plenty of wonder to go around. The mission’s purpose was to ascertain whether Mars had ever had water that might have supported life, microbial or otherwise. (Sorry, no spoilers.) Getting the two Rovers to Mars was itself a miracle of timing and trajectory, “like hitting a golf ball in Los Angeles and trying to hit a door handle in Buckingham Palace,” according to one engineer. Once on the surface, what Spirit and Opportunity “saw” were black-and-white still images of the Martian surface, sent back to Earth along with other data over ten minutes of interplanetary travel time. Which isn’t terribly cinematic, so when “Good Night Oppy” shows us “footage” of the two Rovers making their way across the Martian surface, we’re watching a digital re-enactment, complete with swooping crane shots and dramatic camera angles. The movie’s a crowd-pleasing real-life “Wall-E” in more ways than one, albeit more sentimentalized than the Pixar classic. The score tends toward the tinkly and beatific, and actress Angela Bassett has been cued to narrate in overly reverent tones. Such touches pull “Good Night Oppy” toward the science-museum field-trip end of the spectrum. The individuality and sheer delight of the scientists and the astonishing endurance of the Rovers drag it back toward a real movie, one suitable for thoughtful grown-up engagement and enjoyment.

“Good Night Oppy” is a good movie to watch with older kids, too, especially ones with a math or science bent or who just like taking things apart to see how they work. Almost all of the NASA team members tell White’s cameras about childhood dreams of space exploration, of being driven by curiosity to find things out, and the movie seems to cock its head toward a young viewer as if to say, “You too?” By the final scenes, as Opportunity goes into its second decade – Spirit lasted eight years before conking out in a Martian dust storm – the Pasadena team includes three women scientists who saw the launch as children and teenagers and who signed up in their minds then and there. In its own magnanimous way, “Good Night Oppy” is a recruitment film.

Some critics have carped that the movie goes overboard in its attempt to humanize the Mars Rover program – that it doesn’t let scientists be, you know, scientists. Listening to the actual scientists dispels that argument, simply because they seem so eager to superimpose personalities onto their two “boxes of wires.” When Opportunity’s mechanical joints start to freeze up around Year 10, it’s described as “arthritis,” and when the Rover begins to break down and erase the data collected at the end of each day, it’s likened to the Alzheimers that a grandmother of one of the scientists was diagnosed with at around the same time. Even the communications sent by Spirit and Opportunity were coded to mimic human agency and autonomy, and when Spirit “says” toward the end of her life, “My battery is low and it’s getting dark,” it’s very hard not to think of HAL 9000 in “2001: A Space Odyssey,” mourning a “death” it’s powerless to stop. The movie raises an inadvertent question: Do we need to invest our miracles of science with personalities before we can properly admire them? Would we be less amazed if the robots were just robots without names and facial physiognomy? Would Opportunity be lost?

Thoughts? Comments? Don’t hesitate to share.

If you enjoyed this edition of Ty Burr’s Watch List, please feel free to pass it along to friends.

If you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to sign up for additional postings and to join the discussions, here’s how:

One more thing: The holidays are coming, and what better gift for the movie-besotted loved one on your list than a year’s subscription to Ty Burr’s Watch List?