One Good Film: "The End of Summer" (1961)

For the inauguration of August, a late-period comedy-drama from one of the cinema's greatest masters.

I returned from a few weeks of vacation in Maine on Saturday to a humid night in Boston and the air filled with the chirring of ... cicadas? Crickets? Locusts? I've never been sure which particular orthopteran turns August evenings into a rainfall of soothing white noise, but it's a sound you can feel all the way to the roots of your childhood, to other, long-vanished summer nights that stick in the memory for no other reason than that they balanced on a fulcrum of pure, ecstatic sensation.

Yasujiro Ozu knew this, but, honestly, he seemed to know everything. Regular readers of the Watch List know how deeply I'm in the tank for the great Japanese director (1903 - 1963), whose mature films blur together like Monet cathedrals, each one different and every one the same. Portraits of middle-class comedies and sorrows, gossip and subterfuges and sudden moments of piercing clarity that then move on like clouds over a landscape.

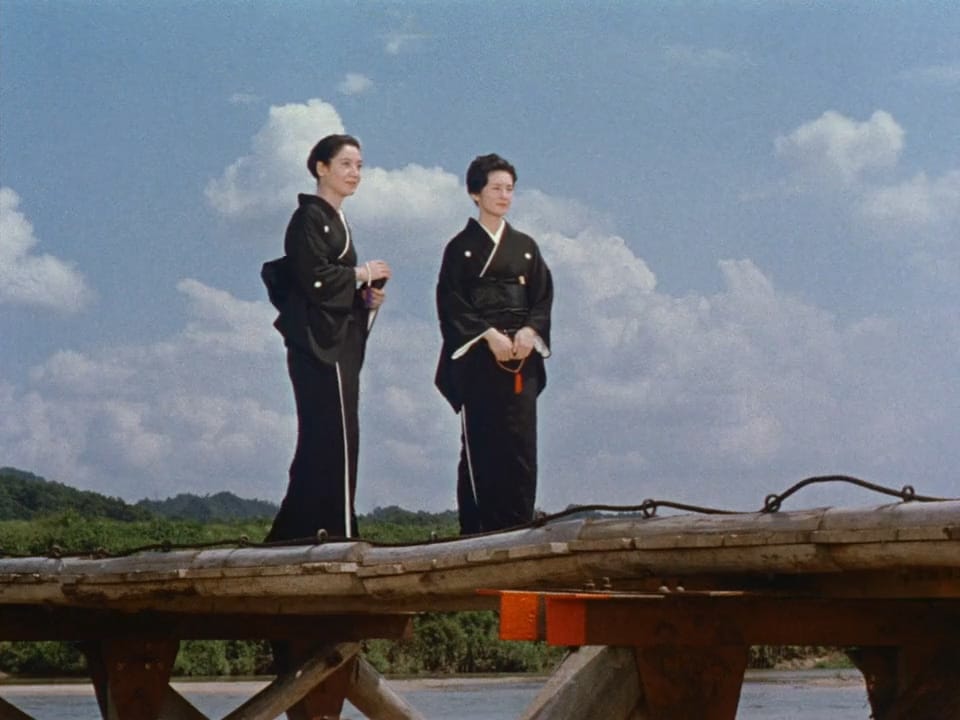

Ozu's penultimate movie is called "The End of Summer" or "Late Summer" (⭐ ⭐ ⭐ ⭐, 1961, streaming on Max, the Criterion Channel, and Kanopy), and all its scenes are alive with that August insect chorus, a constant background hum of the world's turning. The director was famous for his "pillow shots" – static images of vases, empty hallways, trains passing in the far distance, that allowed him to gracefully transition from one scene to the next – and in "The End of Summer," the cicadas function as a sort of aural pillow shot, simultaneously reassuring the characters, lightly mocking them and ignoring them altogether.

The movie follows Manbei (Nakamura Ganjiro II, below), the retired head of a small sake brewery in Kyoto and something of a scandal to his family. Manbei, a widower and a rascal, has a habit of sneaking off for visits with his former mistress (Chieko Naniwa), who has a grown daughter (Reiko Dan) who may or may not be Manbei's. (The daughter is Westernized and always going on dates with American servicemen stationed in Kyoto; they lumber amusingly into this very Japanese movie like a Yeti who've made a wrong turn somewhere.)

Manbei's oldest and most socially self-conscious daughter, Fumiko (Machiyo Aratama), is shocked – shocked, I tell you – and tries to rally the family to rein in the old man's behavior, which goes about as well as you'd expect. A scene where a brewery clerk (Yū Fujiki) is ordered to tail Manbei through the alleys of Kyoto becomes a low-key cat-and-mouse farce.

This being Ozu, "The End of Summer" has other plotlines to cast – a younger daughter (Yoko Tsukasa) who keeps getting set up with suitors she's not interested in, a nosy sister-in-law (Haruko Sugimura, Ozu's go-to shrew), a widowed daughter-in-law (the ethereal Setsuko Hara, in her final film for the master) who seems to see and understand all. And there are the figures on the sidelines who offer humorous commentary and philosophical asides like so many Rosenkrantzes and Guildensterns: brewery workers, a farm couple, and so on. Extras in this story but central to their own. Everything overlaps in an Ozu movie, and everything is also at the exact center of the Venn diagram.

Ozu's last six films are in color, and they are beautiful – the kind of Kodachrome otherworldliness where clothes and household objects glow with their own luminosity. But if you're a newcomer to this director, you may need time to adjust to the calm pace, the low camera placements (the height of a person sitting cross-legged on a traditional tatami mat), and the house style of characters delivering their dialogue straight to the camera rather than to each other. Ozu was a practicing Zen Buddhist (as well as a prodigious boozer and possibly/probably gay), and because the cool, long-view serenity of his movies aligns with my own spiritual/phenomenological ideals, I thought that turning my Zen teacher and friend, Rōshi Bob Waldinger of the Henry David Thoreau Sangha (a.k.a. "Hank"), onto the guy would be a slam-dunk. But this film and the acclaimed "Tokyo Story" (1953) left Bob and his wife ... not cold, but not engaged, not invited into the play and playfulness, and rather confused by that.

I think that's probably a more common reaction than a die-hard would wish, but I understand it. Ozu's narrative style hasn't gone out of fashion because it was never in fashion, a singular branch off the tree of cinema that gets referenced by other filmmakers (Paul Schrader and Wim Wenders among them, the latter's "Perfect Days" a big hit with Rōshi Bob) but that never became a root stock of its own. Maybe you just had to have started watching Ozu early, as I was lucky to do in college. Or maybe you need to catch the right movie at the right time – say, an August viewing of "The End of Summer," with its effortless pirouettes between humor and sadness, the infinity of things and the emptiness beyond, as insects sing in the dark outside your window.

Feel free to leave a comment or add to someone else's.

If you enjoyed this post, please forward it to friends! And if you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to sign up for additional postings and to join the discussions — or just help underwrite this enterprise, for which the author would be very grateful — here’s how.