What To Watch: "Joan Baez: I Am A Noise"

Plus: Gothic noirs on the Criterion Channel, "True Detective," and more.

Plus: Gothic noirs on the Criterion Channel, "True Detective," and more.

[Note: I have a piece in today’s Washington Post about “Perfect Days” and the small but potent genre of Zen movies. Yes, “Groundhog Day” makes the cut. Here’s a free link if you’d like to read it.]

Having long been fascinated by the gulf between celebrity personas and the smaller, more complicated human beings that lurk behind the false fronts of fame, I find that “Joan Baez: I Am a Noise” (2023, ⭐ ⭐ ⭐ 1/2) is unexpectedly my jam. The documentary starts streaming on Hulu this week while continuing to be available for rent on Amazon, Apple TV, YouTube, and elsewhere, and whether or not you’ve ever been partial to Baez’s image as the sainted Madonna of the 1960s folk and protest movements, the movie is worth a look as a raw and intimate portrait of debilitating vulnerability. The film yaws between the singer’s farewell concert tour in 2018, at the age of 79, and a bursting storage unit of personal archives stretching across Baez’s life, from childhood to the present day. Co-directors Miri Navasky, Karen O’Connor, and Maeve O’Boyle are apparently long-time Friends of Joan, and while closeness between filmmakers and subject can often sand the warts off a documentary, in “I Am A Noise,” it allows for shockingly personal confessions of inadequacy, depression, panic attacks, egotism, heartbreak, and more. We hear Baez the elder on the soundtrack co-existing with a younger Joan in audiotapes made from adolescence onward, testifying to a hurtling rollercoaster of emotional ups and downs. Where most music documentaries are chronological re-caps of a career, this one is a psychographic chart of lifelong distress, not so much “Behind the Music” as “Behind the Mask.”

And a mask it was, rigid with that crystalline soprano and the political righteousness of youthful idealism. Baez was a national star at 18, on the cover of Time at 21, and the source of her appeal was her unwavering certainty and moral rectitude – she was the voice of the coming counterculture as it grew strength and took aim at the rotten framework of the parental culture. “I went from thinking I wasn’t very adequate to being called the Virgin Mary,” Baez recalls, and she didn’t have the nerve or the daredevil imagination to push back against the typecasting. Few would have; maybe only Bob Dylan did. It’s clear in “I Am A Noise” that Baez is still haunted by their brief relationship – “I was just stoned on that talent,” she says, and they seem very much in love singing “It Ain’t Me, Babe” on stage in Newport in 1964. It must have been truly disorienting to come into the affair the bigger star and leave it the lesser figure. “He was just a person then, and a kid,” Baez says, neglecting to mention that she was, too.

Dylan instantly rendered Baez and the entire first wave of folkies obsolete by writing his own songs, singing them with rough individualism rather than imitative earnestness, and in general being vividly present instead of reverentially looking to the past. He was also funny, at least in the early days, which is something most of the Greenwich Village/Newport scene, from Pete Seeger on down, were far too doctrinaire for. You can hear Baez being drawn to his humor, his uncontainable sense of life, in her memories, and once it went away – Dylan pretty much ditched her in England during his 1965 tour – she rerouted her energies into activism: the Civil Rights movement, protests against the Vietnam War, pushing for prison reform, and other necessary actions.

The music suffered. 1975’s best-selling “Diamonds and Rust” aside, Baez has always been more of an interpreter than a confessor, and an interpreter within fairly strict limits. (A performance of Tears for Fears’ “Shout” from the 1986 Amnesty tour is, to put it very kindly, ill-advised.) Which is what makes “I Am A Noise” so continually surprising. It is, in a sense, the singer-songwriter album that was hiding inside Baez all this time, terrified of being revealed and of being seen as unholy and unworthy as she herself felt.

There are casualties along this journey, some more disturbing than others. Joan’s older sister Pauline is seen in warm and honest conversation before her death from cancer in 2016; younger sister Mimi (Baez) Fariña, who died in 2001, is remembered as a deeply sad woman who never really recovered from the death of her husband and musical colleague Richard Fariña in a 1966 motorcycle crash. Dylan “broke my heart”; husband David Harris “was too young and I was too crazy”; son Gabriel Harris, a supportive presence on the farewell tour, nevertheless recalls “missing the closeness of a family” while his mother “was too busy saving the world.”

And then there are the extremely vague accusations of sexual abuse at the hands of father Albert Baez, accusations that arose from the singer’s sessions in the early 1990s with a therapist specializing in now-debunked recovered-memory techniques and which Albert and Joan’s mother strenuously denied to the end of their days. Mimi, too, had memories of an overly intimate paternal kiss, and there’s an entire movie excavating the truth of what happened that neither Joan nor the filmmakers seem willing to grapple with. Which is a shame, one that extends to the entirety of this curious, brave, blinkered, and unsettling documentary. Behind the plaster saint of her public image, Joan Baez was a mass of contradictory emotions and whipsawing self-worth. Imagine if she had applied even a little of that to her art.

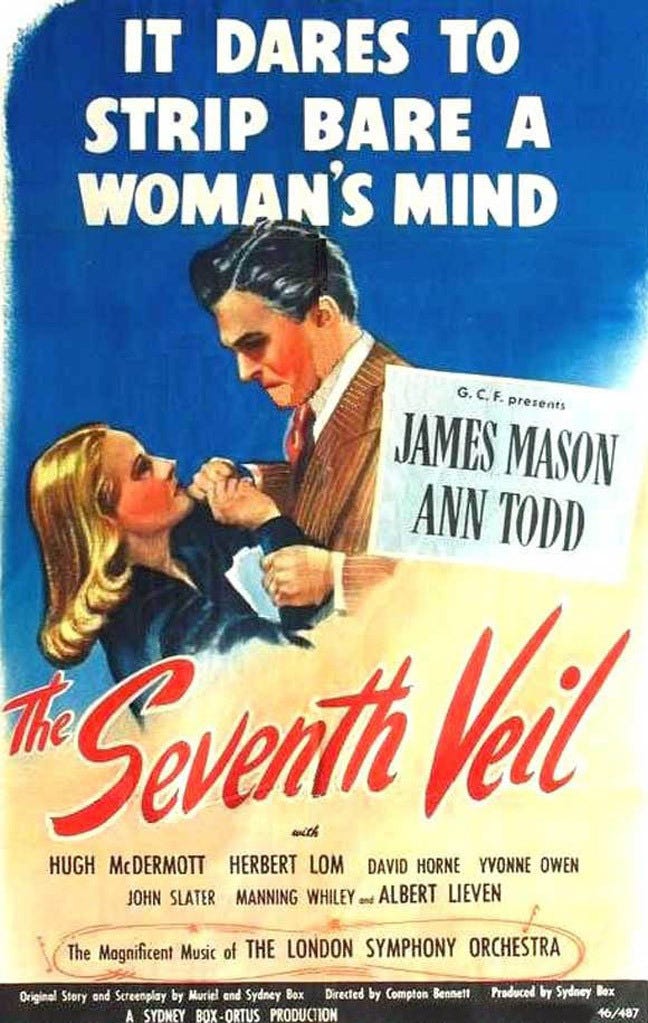

For that hopefully large Venn Diagram subset of my subscribers that also subscribes to the Criterion Channel: The service’s Gothic Noir festival is a pip. Twelve black-and-white classics from 1944 to 1951 that place tough-minded heroines into stark, misty thrillers and suspense dramas. Start with the labyrinthine “My Name is Julia Ross” (1945, ⭐ ⭐ ⭐ 1/2), in which Nina Foch is hired as a lady’s companion at a country estate plagued with murderous relatives, then move onto the enjoyably demented “The Seventh Veil” (1945, ⭐ ⭐ ⭐), in which Ann Todd plays a concert pianist undergoing therapy thanks to her sadistic-yet-hot guardian James Mason – kinky stuff for 1947. “Lured” (1947, ⭐ ⭐ ⭐ 1/2) is early Douglas Sirk before he broke into wide-screen Technicolor melodrama; it stars Lucille Ball in a witty turn as a showgirl going undercover to trap a murderer and has a freaky sequence with Boris Karloff as a fashion designer who’s lost his marbles. “Ministry of Fear” (1944, ⭐ ⭐ ⭐ ⭐) is Fritz Lang adapting one of Graham Greene’s “entertainments,” a fine spy story. The only ringer in the series, as far as I can see, is “Undercurrent” (1946, ⭐ ⭐), a passable suspense noir that casts Katharine Hepburn – who was made for many genres but not this one – as a wallflower who marries a sleazy industrialist (Robert Taylor?!) before falling in love with his idealistic brother (Robert Mitchum?!?) Also, I’ve always wanted to see “Kiss the Blood Off My Hands” (1948) based on the title alone – not to mention Burt Lancaster, Joan Fontaine, and a fog-swirled London setting – and now’s my chance and yours.

Longtime subscribers may remember my post commemorating my father-in-law on his passing in August of 2022 and, specifically, my memories of watching a final film with him, the delightful George Stevens romantic comedy “The More The Merrier” (1943, ⭐ ⭐ 1/2), starring Joel McCrea, Jean Arthur, and Charles Coburn as a senior-citizen Cupid. It’s on Turner Classics on Saturday night (March 17) at 10:30 p.m., and if you’ve never seen it, you really should. Do it for Marty.

Like many restless TV watchers, we at the Burr house have been taking in HBO’s “True Detective: The Night Country” (2024, ⭐ ⭐ ⭐ 1/2), and while it’s great to see Jodie Foster (above right) in a juicy extended starring role, I am more than ready for this series to come to a close on Sunday night. It is guilty along with a great many other shows in this Golden Age of Peak TV of dramatic dog-paddling, telling a story in six hour-long episodes that could have been told in four and maybe even two. That length just means the writing has to hammer on character traits more than twice when once is often enough: Foster’s character’s loose ways in the sack, the junior cop played by Finn Bennett’s overzealous job dedication at the expense of his marriage, Trooper Navarro (Kali Reis, above left) glooming and dooming over her tragic family legacy. The performances are excellent and the midnight arctic setting unique, but there’s a point when mood just turns into vamping, and we passed that point back in Episode Three. Caveat: Mrs. Movie Critic disagrees with this opinion and so may you.

Leave a comment!

If you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to sign up for additional postings and to join the discussions — or just help underwrite this enterprise, for which the author would be eternally grateful — here’s how.