What to Watch: "Lime Kiln Club Field Day" outtakes

On Bert Williams, early Black film, and the road not taken.

A note to readers: Between getting ready for the Toronto International Film Festival next week and writing five pieces for the Washington Post this week – three reviews, one thumbsucker on smart-home horror films, and one TIFF run-up/round-up – I haven’t had much time to pen any new Watch List posts. (The first two of the reviews, for the Dennis Quaid “Reagan” biopic and the Casey-Affleck-goes-crazy-in-space thriller “Slingshot,” can be read by following the linked titles to the WaPo or in this post below the paywall. I’ll send out the rest in a separate post.) But I did want to point out a film or, really, group of films, that have recently landed on The Criterion Channel and that are of immense historical importance and, in their way, intensely moving.

I’ve been fascinated by Bert Williams for many years now, a man forgotten by popular culture when I was coming of age in the last half of the 20th century but who has been rediscovered and reclaimed in recent decades thanks to the internet, determined academics and entertainment figures, the reissuing of his recorded legacy, and some felicitous archival finds. No one is more deserving: Williams (1874-1922) was the first Black entertainer to appeal to both Black and White audiences, was internationally famous, was one of the very first recording artists to sell in major quantities – again, to all audiences – and was an early movie star to boot.

He was the first Black entertainer to headline the Ziegfeld Follies (from 1910 to 1919), over the initial objections of some of his White co-stars, to whom Flo Ziegfeld said, “I can replace every one of you except him.” Williams and George Walker, his performing partner for the early part of his career (and a fascinating subject in his own right), brought the first all-Black musical, “In Dahomey” to Broadway in 1902 and took it to London, where they gave a command performance at Buckingham Palace. Williams’ signature song, the doleful “Nobody,” sold as many as 150,000 copies, a huge amount for an early wax cylinder recording. (It’s since been covered by everyone from Bing Crosby to Nina Simone to Johnny Cash to Cécile McLorin Salvant to Gonzo of “The Muppet Show.”)

And Williams appeared in movies, as was fitting for one of the most well-known stage stars of his era. He made at least two for the Biograph film company, “A Natural Born Gambler” (1915) and “Fish” (1916), which, in an acknowledgment of his stature, Williams wrote, produced, directed and starred in. Earlier, though, he had appeared in a joint production of Biograph and the stage producers Klaw and Erlanger, a comedy about a Black social organization that was never completed or titled. The negative wound up in the vaults of the Museum of Modern Art in the late 1930s, a print was finally struck in the 1970s, and in the new millennium archivists assembled a rough finished version and, in 2014, presented it to MOMA audiences as “Lime Kiln Club Field Day.”

That’s what is now available on The Criterion Channel: The reconstructed hour-long “Lime Kiln Club Field Day,” plus a 20-minute conversation, taped in 2024, between MOMA curator Ron Magliozzi and Jacqueline Stewart, University of Chicago cinema professor and former director and president of the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures. On top of that, there’s also 7-1/2 minutes of outtakes from the filming of “Lime Kiln Club Field Day.”

It’s the last item, oddly enough, that to me is the most affecting, but I’ll get to that in a bit, after I address the elephant in the room.

The shock of modern viewers coming to Bert Williams for the first time, of course, is that he’s a Black man who wore blackface. This was and remains the chief irony of his career, and one of which he was fully and painfully aware. Without getting into the larger history of minstrelsy, the inherently racist practice of White entertainers disguising themselves as crude caricatures of Black people, let me repurpose some passages from a piece I wrote in the Boston Globe back in 2007 (no longer available online), after watching an anniversary DVD reissue of “The Jazz Singer”:

By the 1840s, with the massive Broadway success of the Virginia Minstrels - four "blacked-up" white men presenting an evening of "the oddities, peculiarities, eccentricities, and comicalities of that Sable Genus of Humanity" – [minstrelsy] was established as the chief conduit by which white audiences perceived black American life. … It served as a tool for the white mainstream to appropriate and “tame” various representations of black people - to reduce the race to a populist cartoon that delivered spirituals and other "coon" culture in a way that would have been unacceptable coming straight from the source.

Using the sentimentalized plantation songs of Stephen Foster and others, blackface troupes like E.P. Christy's Christy Minstrels boiled the miseries of slavery into a recognizable ethnic caricature that assuaged white guilt by turning it into the music of comedy and pathos.

Early minstrelsy also denied African Americans a chance to express their own art in the mainstream by handing that art over to white songwriters and performers who diminished it in a bid to gain "soul." (Sound familiar?) Some commentators of the day were astute enough to pick that up. Frederick Douglass himself blasted the form as "sporting over the miseries and misfortunes of an oppressed people." But Douglass also thought the songs of Foster expressive of "the finest feelings of human nature," and he lavished praise in 1849 on Gavitt's Original Ethiopian Serenaders, a minstrel troupe made up of black artists.

Yes, Virginia, there were black minstrels, and plenty of them. They wore blackface, too. The most celebrated, even beloved, was Bert Williams, who starred in the Ziegfeld Follies from 1910 through 1919 and who Booker T. Washington once said "has done more for our race than I have. He has smiled his way into people's hearts; I have been obliged to fight my way."

Allow me to interpolate here that Percival Everett’s remarkable new novel, a re-envisioning of “Huckleberry Finn” called “James,” addresses the cultural cruelties and individual indignities of minstrelsy within a period-appropriate frame and without an iota of patience for the hypocrisies of the White overculture. (Indeed, it extends minstrelsy to the entirety of Black slave life, an exhausting, never-ending act of code-switching.)

… It helps to think of minstrelsy in general and blackface in particular as a mask, one that rightly or wrongly allowed a performer to say things about black culture that wouldn't be accepted otherwise. At first, only whites were allowed to wear the mask. Then African American artists began to put it on because it was the only mask available. The difference is that they were able to express certain coded truths through songs and comedy that white audiences weren’t able to pick up on. They were also earning a living in front of black and white audiences - American audiences. They were being heard.

Bert Williams is part of that gradual reclaiming of Black artistry from White entertainers, and a crucial one, but to be heard, he (and George Walker) had to cork up – had to function as Black entertainers wearing a mask of racist Black caricature. Ironically, William saw himself as an outsider to both groups: A Bahamian-born Caribbean American, he was light-skinned enough that Ziegfeld Follies audiences would have been confused to see him without blackface. (In a sense, he truly was “nobody.")

The legend that has built up around Williams over the decades is that he was a modern Pagliacci, a clown crying behind the make-up – in the words of W.C. Fields, who worked with him in the Follies, “the funniest man I ever saw – and the saddest man I ever knew.” But “Lime Kiln Club Field Day” (and, to a lesser extent, “A Natural Born Gambler”) doesn’t square with that tragic persona. As assembled by the MOMA curators, without intertitles but including multiple takes of individual scenes, “Field Day” is a showcase for Williams’s comic stage business and – even more important – a glimpse of an interracial film industry that was strangled in its infancy.

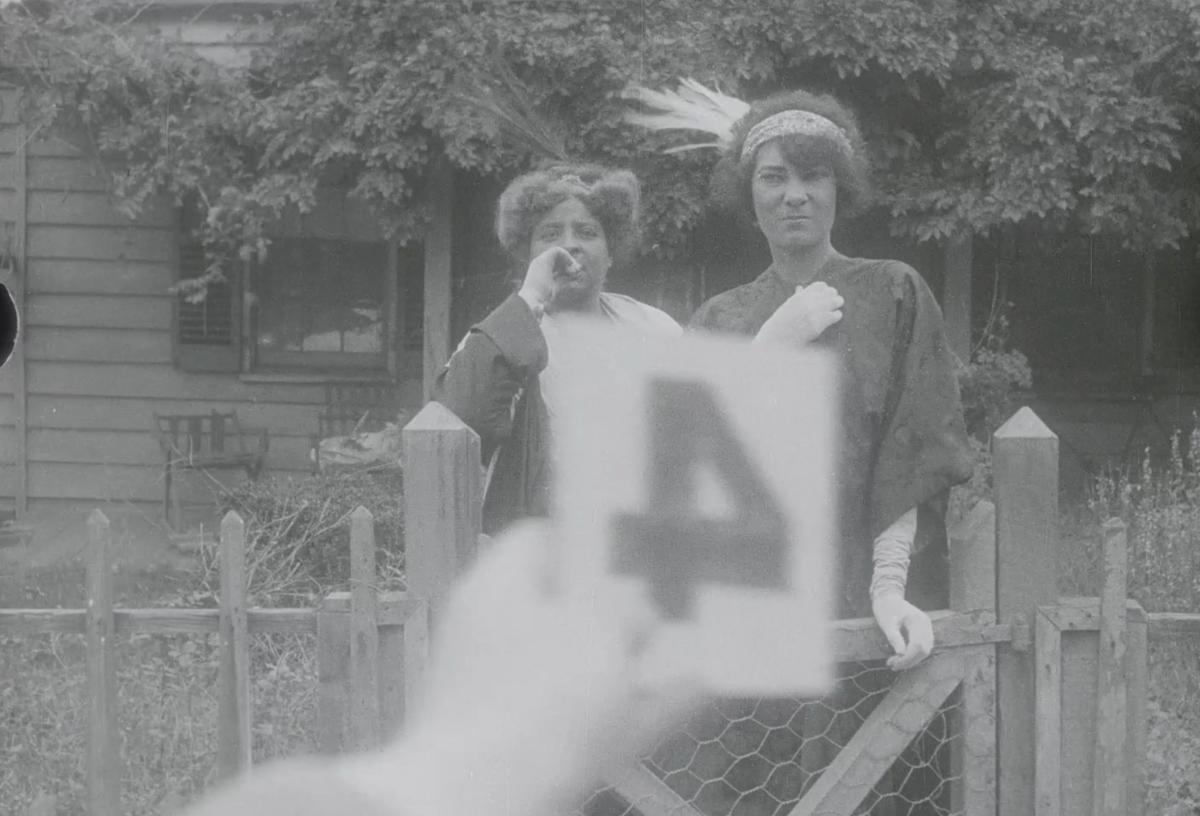

Skit-like in structure, “Field Day” concerns the rivalry of various members of the fraternal order of the Lime Kiln Club to woo a local beauty (played by Odessa Warren Grey, a Harlem actress, milliner and socialite). Much of the action takes place at a country picnic field day, with Williams’ rascally suitor employing various tricks to outfox his fellow club members. He’s the only character wearing blackface; in the context of the era it’s as integral to him as The Tramp's derby, shoes and cane were to Chaplin – a brand. And he’s funny, his body language, expressions and precision timing the result of decades of finely-honed stage experience.

Notably, none of the other actors in “Lime Kiln Club Field Day” is in blackface and they’re presented with few of the racist stereotypes we associate with the period. The movie plays as a broadly comic but essentially realistic view of middle class Black life in the years immediately predating the Harlem Renaissance, and the relationship between Williams and Grey is portrayed with uncaricatured affection, up to and including a long fade-out kiss that would have been unthinkable even a few years later.

So what happened? “The Birth of a Nation” happened. D.W. Griffith’s 1915 blockbuster codified the racist archetypes that would dominate American cinema until at least the post-WWII era by casting White actors in “realistic” (i.e., non-minstrel) blackface for major roles while Black performers were relegated to background extras. “Nation” is responsible for a whole lot of bad mojo, the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan not least of all. But the snuffing out of a vision of Black self-expression and interracial industry cooperation that can be seen a-borning in “Lime Kiln Club Field Day” is one of the sadder unknowns, a fork in the road that was never explored.

That’s why, for me, the seven minutes and forty seconds of outtakes from the production of “Lime Kiln Club Field Day” have a power that comes from the most profound of What Ifs. The segment isn’t much, really – just snippets of set-ups for scenes, the moments before the directors called “action” and after they called “cut,” cast and crew milling about the sets as they relax and work out business. (“Lime Kiln Club Field Day” had three directors: Edwin Middleton and T. Hayes Hunter, who were White, and assistant director Sam Corker Jr., who was Black.)

It’s that banal, un-performative normality – a window onto people living their lives, pursuing their craft without regard to race or racism – that I find terribly emotional. We glimpse Harlem -based actors Sam Lucas, Abbie Mitchell, J. Leubrie Hill, Emma Reed, John Wesley Jenkins, Walker Thompson and Billy Harper talking and laughing; unnamed Black and white crewmembers weaving in out carrying lights and the era’s version of film clappers; Bert Williams in blackface but out of character discussing an upcoming take with one of his White directors. It’s what would have, could have, should have been: A collaboration that led to greater film industry engagement and – who knows? – social progress.

Instead, unsurprisingly, Black filmmaking diverted into “race films,” with directors like Oscar Micheaux creating movies on Black topics with Black actors for Black audiences that went unseen by the majority of White audiences and unnoticed by the White media. One hundred and eleven years after it was shot, “Lime Kiln Club Field Day” serves as a reminder that less than half a century after the end of slavery, another way came and went.

Enjoy your weekend, and feel free to leave a comment or add to someone else's.

If you enjoyed this post, please forward it to friends! And if you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to sign up for additional postings and to join the discussions — or just help underwrite this enterprise, for which the author would be very grateful — here’s how.