What to Watch: Present, Tense

Kelly Reichardt's "Showing Up" is about art for heart's sake. Plus: "Hilma," "Tori & Lokita," "Mafia Mamma," and more.

One of the great magic tricks of the movies is to seduce us into an imagined present. In the actual present, we’re sitting in a movie theater eating Junior Mints or skootched back on the TV room couch at home, but all that drops away when the story is good and the characters seem real and an onscreen world built from edited scraps of captured time fools us into believing that what we’re watching is happening right now. Every movie or TV show – every filmed entertainment – unfolds in the present tense, even the flashbacks. Every movie or TV show is an amnesia machine that wants us to forget where we are so it can take us to where it wants to go. That can be Rick’s Café Américain in a Warner Brothers backlot Casablanca or the wedding of Don Corleone’s daughter in a post-war Long Island or even an immigrant Chinese laundrywoman surfing the Multiverse, but wherever the movie is happening, it’s always “here.” It’s quite the illusion.

Some movies lean harder into the presence of this chimerical present – they slow down and look around, letting plot come as it may while allowing us to feel the air of a two-dimensional world against our skin. Many audiences are discomfited by this approach and push back: Without the distraction of a strong narrative, the illusion can reveal itself as such, and no one wants to admit they’ve been fooled. Others viewers welcome the immersion and learn to trust those filmmakers who have the faith to trust us. Kelly Reichardt is one of the foremost architects of cinematic places in which things happen and through which characters move but that are charged with atmospheres of their own design and are committed to exploring them with patience and curiosity. Her latest film, “Showing Up” (⭐⭐⭐1/2), expands today from New York and L.A. to independent theaters across the country, and it’s about nothing more or less than how art gets made. Movies usually present the act of artistic creation as a mystical climax, the paint on the canvas conspiring with the music on the soundtrack to come dramatically together in just the right way for genius to be birthed. In “Showing Up,” art is what happens when no one else is paying attention. It’s a drudgery and also the only reason to get up in the morning.

The film marks Reichardt’s fourth collaboration with actress Michelle Williams, who you may be forgiven for seeking out in vain on the screen. No, that’s her, right there – the mousy, sullen woman in the granny dresses with potter’s clay all up her arms. Lizzy. Who works in the administrative offices at a Portland, Oregon, art school that her mother (Maryann Plunkett, a treasure of the American stage) helps run. Who lives in a dingy apartment she rents from Jo (Hong Chau, hooray), a fellow artist with all the confidence, joie de vivre, entitlement, and success that Lizzy lacks, and who also is at least a week behind in fixing Lizzy’s hot water heater, which has kicked Lizzy’s general annoyance with the world up a DEFCON level or two.

The movie’s “present” is the art school itself, busy with young people making visions out of whole cloth and other materials and with instructors like Eric (André Benjamin, a.k.a. André 3000) helping out. There’s a large and presumably ancient dog that everyone steps over to get into the main office, and it’s typical of Reichardt’s gossamer touch that the dog is never remarked upon – he or she is just there, beloved furniture. The director has a way of inviting the animal kingdom into her movies: Her first film with Williams was “Wendy and Lucy” (2008), in which Lucy is a dog, and her most recent work before “Showing Up” was “First Cow” (2019), which is about dueling visions of America’s pioneer urge and also about a cow.

Reichardt likes to watch, and the new movie is at its most serene when it parks the camera next to a student working on a painting or a pot or an installation or a dance and just lets the footage run. What does making art look like? It looks like work; it looks like joy; it looks like oxygen. Lizzy’s life is a series of hurdles to crank past on her way to her own art opening: Her highhanded landlord, her ditzy mother, a feckless artist father (Judd Hirsch), a bi-polar brother (John Magaro of “First Cow,” scary and intense). A noodgy cat, too and a wounded pigeon that for my money is the one false move in “Showing Up,” because it’s less a pigeon than a big, clanky Metaphor, and Reichardt doesn’t do metaphors, or shouldn’t. The movie is finally about what it wants to be about when Lizzy knuckles down and gets to work in the evenings, fashioning clay figurines of women in poses that feel like small emotional explosions. Shame. Shyness. Frustration. Ecstasy. We watch the work take shape over the course of the film, our respect for this prickly and private woman growing with each step: The sculpting, the mounting, the glazing. One of the pieces gets scorched in the kiln, and when Eric advises her to accept the chance of error into her art, you can see that idea percolate down into Lizzy’s soul, too (and more organically than the business with the pigeon).

The art opening, when it comes, is a gentle farce of family miscommunication, but it’s also the present that the movie’s other scenes of presence have been working their way toward – the moment when all the characters in “Showing Up” crowd into a Main Street gallery, drink cheap white wine, and acknowledge the small, fragile women that Lizzy has created as well as the woman behind them. Do people make art for it to been seen by others or simply because the making of it is purpose enough? Reichardt, as she does so often, leaves the matter open to argument, and you realize the movie itself is part of the same dialectic. The pleasure she and Williams and the cast and crew seem to have taken in making “Showing Up” is separate but inextricable from the pleasure we have in watching it – from being in its presence.

Coincidentally, another film about an artist arrives in theaters today: “Hilma” (⭐⭐), about the life of Hilma af Klint, whose work, while rooted in her Theosophist spiritual beliefs, prefigured abstract painting by several decades. Directed by Lasse Hallström (“Chocolat,” “What’s Eating Gilbert Grape”), it’s a handsomely mounted and rather stiff affair, attentive to the line where Hilma’s mysticism shades into monomania — lead actress Tora Hallström, the director’s daughter, struggles to convey both sides of the coin — but much less uninterested in the processes, the work, that gives “Showing Up” its buoyancy.

An air of watchfulness breathes through “Tori & Lokita” (in theaters, ⭐⭐⭐), too, but it’s a breath that catches in your throat. The title characters are two young West African immigrants living by their wits in the Belgian city of Liege. Eleven-year-old Tori (Pablo Schils, above right) is street smart and a skilled negotiator; he has papers allowing him to stay in the country, but 16-year-old Lokita (Mbundu Joely, above left) doesn’t, and the two try to convince the authorities they’re brother and sister while running weed for a sleazy chef and trying to pay back the smuggler that arranged for Lokita’s passage. The directors are Belgium’s Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, who have built a towering filmography of stories about the dispossessed over three decades. Some of those films offer hope (“The Kid with a Bike,” 2011), others flatten you with despair (“Rosetta,” 1999), and all of them are profoundly compassionate in their naturalism – they invite us to see people where we’d feel more comfortable seeing statistics. “Tori & Lokita” is no different except in the measure of indignities it piles upon its young heroes – turns of plot where, for once, you feel the hand of the filmmakers on the controls and sense those hands shaking with rage. Which, at the end of the day, may be more our problem than the Dardennes’.

Certain movies you watch while wondering “Why on earth is [Respected Star] appearing in this dreck?” before you realize, “Oh, they got a free vacation out of it.” So it is with “Mafia Mamma” (in theaters, ⭐ 1/2), which allows Toni Collette to slum it in a broad, bumpy farce about a super-basic California mom who learns she’s heir to her Italian grandfather’s mob family and related vendettas. Enjoyably dumb in places but mostly just dumb, it’s basically “Under the Tuscan Sun” with live ammunition. Collette got to go to Europe and all we got was this lousy movie.

By contrast, two of 2022’s best films have arrived on streaming platforms: “The Quiet Girl” (⭐⭐⭐⭐), Ireland’s Oscar nominee for Best International Film and a miracle of presence as seen through the eyes of an unwanted girl finding her people, is available for a $6 rental on Amazon, Apple TV, YouTube, and elsewhere, while “No Bears” (⭐⭐⭐⭐) — the latest this-is-not-a-film from the Iranian master Jafar Panahi — debuts on The Criterion Channel April 18. The latter is a metafictional tragicomedy worthy of Kafka; Panahi would have been present at its Venice Film Festival premiere last August, but he was busy being a prisoner of the Iranian government. (He has since been released.)

Classic of the Week: Crime Wave (1954, ⭐⭐⭐), airing on Turner Classics Sunday at 11:30 a.m. but also available as a cheap rental on Amazon, AppleTV, and YouTube, is exemplary noir — fast, tough, and tight as a drum at 73 minutes. Gene Nelson plays an ex-con gone straight who gets sucked back into crime when some old pen pals come to town, but the film’s most notable for Sterling Hayden exuding his usual self-disgust as the cop on the case and for three great supporting performances: Timothy Carey as a giggling creep, Jay Novello as a drunk veterinarian with a sideline in patching up gangsters, and, as a muscle-headed hood, a young actor named Charles Buchinsky who would soon be changing his name to Charles Bronson. Directed without an ounce of fat by André De Toth, the only one-eyed filmmaker to ever direct a 3-D movie (“House of Wax,” 1953).

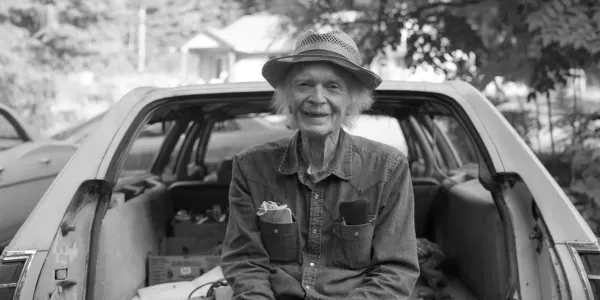

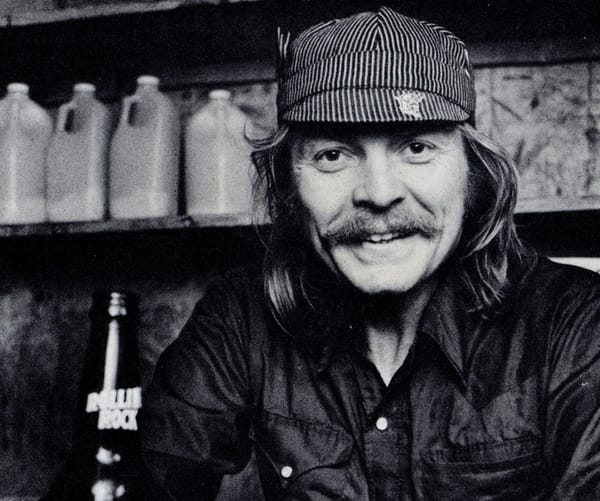

Lastly, tonight on Showtime brings us the premiere of “Personality Crisis: One Night Only,” a Martin Scorsese-directed concert film featuring the estimable and legendary David Johanson, who some people are convinced is an alter ego of 1990s retro-showman Buster Poindexter and others swear was the rocket engine that propelled the New York Dolls, the band all the rock snobs hated in 1973 but that seeded the ground for every punk and New Wave act to come on both sides of the Atlantic. I haven’t seen the new special so I can’t rate it, but you’d better believe I’ll be watching it, along with the ghosts of the Dolls, of whom Johanson is somehow the last man standing. (The curious are also directed to “New York Doll,” ⭐⭐⭐, a funny, heartbreaking documentary about the band’s bass player Arthur “Killer” Kane, who went from being one of rock’s true wild men to a converted Mormon working in the LDS genealogical library on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. It’s a two-buck rental on Amazon.)

Thoughts? Don’t hesitate to weigh in.

If you enjoyed this edition of Ty Burr’s Watch List, please feel free to pass it along to friends.

If you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to sign up for additional postings and to join the discussions — or just help underwrite this enterprise, for which the management would be very grateful — here’s how.