What to Watch This Weekend 10/15/21

"The Velvet Underground" on Apple TV+ and "The Last Duel" in theaters

The Nut Graff: Todd Haynes’ music doc is a loaded gift for Velvet Underground fans (***1/2 out of ****); “The Last Duel” is a moral swashbuckler with meaty performances. (*** out of ****)

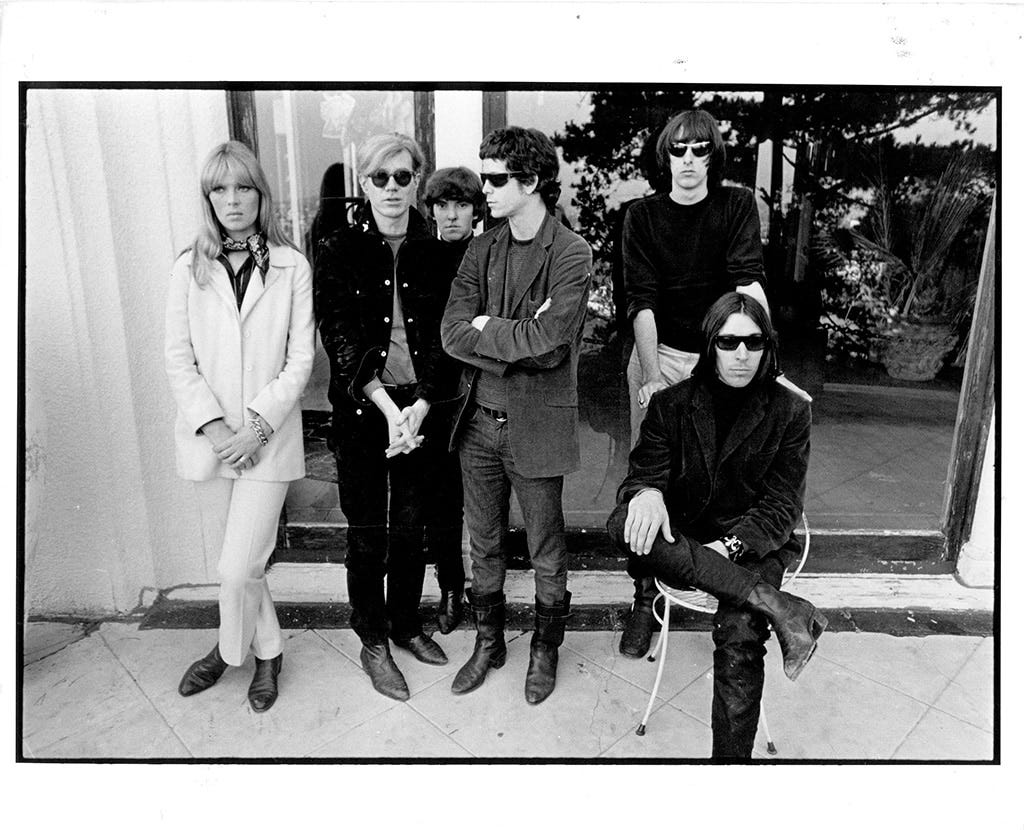

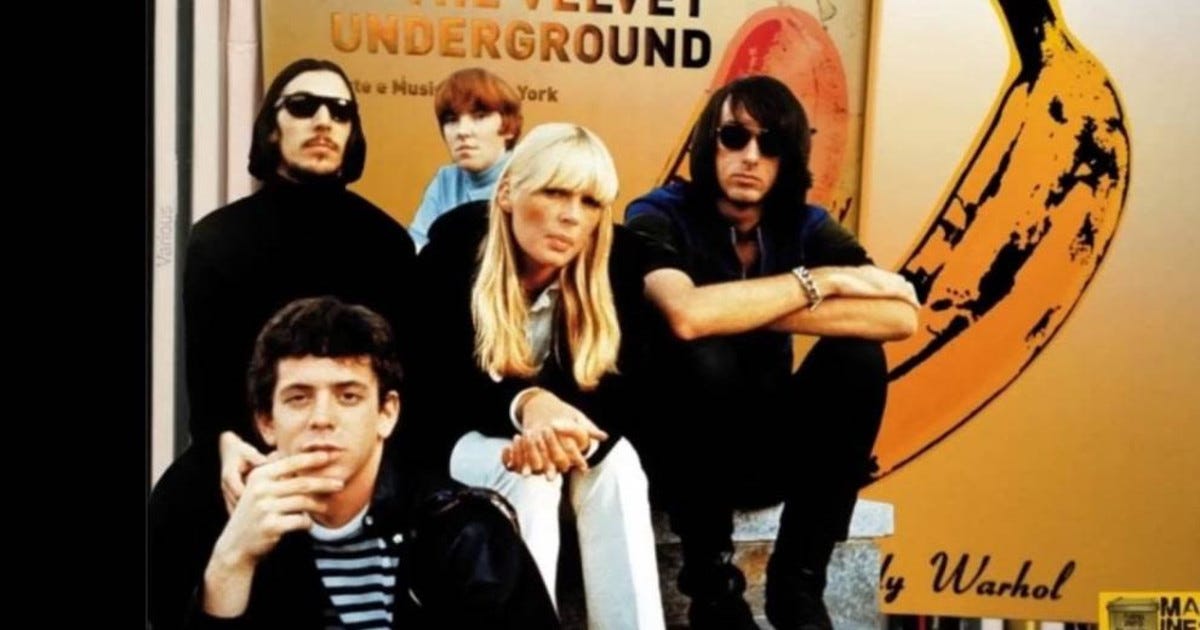

From the extra-legal “Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story” (1987) to the brilliant, hydra-headed Bob Dylan biopic “I’m Not There” (2007), there may be no better director than Todd Haynes at dramatizing the weird, dark heart of American pop music. (Exception: 1998’s “Velvet Goldmine,” which crossed the pond to glam-rock England with sludgy results.) The man knows his deep cuts – who else would put Fripp & Eno’s dreamy “Evening Star” in a kids’ adventure movie (albeit one for grown-ups)? – and his new documentary “The Velvet Underground” is a fond and clamorous embarrassment of riches, one that recreates the early-60s maelstrom that birthed the group. If you’re a newcomer, the movie will seem like a tsunami of information – it’s not the best place to begin. (The records are.) But if you hold this music and the vanished New York City it invokes close to your soul, “The Velvet Underground” feels like a creation myth.

The Velvets, of course, invented alt-rock. Without them, no punk, no post-punk, no folk-punk, no Goth, glam, emo, indie, industrial, shoegaze, grindcore, queercore. Every musical outfit that locates beauty in noise, or understands the importance of drone, or seeks company with the outcast and broken traces its DNA back to VU. They were smashing plates in the studio and singing about transsexuals and heroin in 1966. It took a long time for the world to catch up, in part because everybody who heard “The Velvet Underground and Nico” felt like they’d discovered it alone, usually late at night when the normal world was asleep. But, to paraphrase Brian Eno (or somebody), each of those misfits went out and started a band.

Haynes dives deep into the roots of the group, and he sketches the milieu with a hardcore fan’s attention to detail. VU patron/“producer” Andy Warhol doesn’t show up until minute 51 of the two-hour documentary; Nico, the first album’s spectral chanteuse, arrives at the halfway mark. The audience is given a thorough grounding in Lou Reed’s Long Island rebellions and early sonic assaults and in the downtown art scene that was bubbling over with mavericks of film (Jonas Mekas, interviewed not long before his death in 2019 at 96) and music (La Monte Young, who’s alive and kicking at 85, a gray-maned shaman of the loft scene). The editing is a heady amphetamine rush that avails itself of both Warholian split screens and Warhol screen tests, those confrontational close-ups of everyone who was anyone in the era’s overlapping Venn diagrams. The remaining Factory survivors are present to tell their tales, including Mary Woronov, as regal as ever. Longtime film critic Amy Taubin (Film Comment, The Village Voice) is here both in her screen-test youth and as a wise elder drily noting that the scrum of sex and drugs and fame-whoring around Andy was “not good for women.”

So it’s a clear-eyed view, and part of that clarity is re-emphasizing how crucial John Cale was to the enterprise. Guitarist Sterling Morrison was the backbone and drummer Maureen Tucker the steady, enduring pulse, but Lou and John were the brain trust, the former a self-taught bad boy penning lyrics about dope and transgression while hoping desperately to become a rock star, the latter a classically trained Welshman with a love of chaos. (The young Cale was also a guest on the TV game show “I’ve Got a Secret”; the clip starts the movie and can be found on YouTube.) The demimonde sensibility behind songs like “I’m Waiting for The Man” and “Venus in Furs” might have been Reed’s but the sound – the yawing viola and pounded piano, the cacophony and drone – were very much Cale’s brief, and when an insecure Lou booted him out of the band after the second album, the experimentalism went with him. (The self-titled third album, recorded with the unthreatening Doug Yule replacing Cale, is muted, pretty, and haunted.)

Morrison died of lymphoma in 1994 and Reed passed away in 2013; they’re ghosts in the film’s machine in the form of archival interviews. Neither Warhol nor Nico made it out of the 1980s. Cale and Moe Tucker are excellent company, though, as are others who were present at the fire, including Jackson Browne, who was 19 when he briefly signed on as Nico’s songwriter and lover. “The Velvet Underground” is not so much a music doc as an attempt to resurrect a lost time and place and the lost men and women in it – the sound and look of it, the loneliness and joy. It’s the closest you can come to a Manhattan madeleine — one bite and it all comes inevitably swirling back.

“The Last Duel” arrives in theaters today, and, lo, it’s pretty good. Better than I was expecting from a knights-in-armor epic starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck, anyway. The two wrote the script – their first collaboration since “Good Will Hunting” a quarter century ago – along with co-writer Nicole Holofcener. Holofcener has directed some very good modern dress comedy-dramas over the years – “Lovely and Amazing” (2001), “Friends With Money” (2006), James Gandolfini’s penultimate movie “Enough Said” (2013) – and her participation is critical to the “Rashomon”-style structure of “The Last Duel.”

Set in 14th-century France and based on true events, the movie is first told from the point of view of the battle-scarred Jean de Carrouges (Damon) as he challenges a silky rival, Jean le Gris (Adam Driver), to a duel to the death after the latter rapes de Carrouges’s wife, Marguerite (Jodie Comer). It then replays the events from le Gris’s perspective and finally shows them through Marguerite’s eyes. What is first presented to us as a crime against a man’s property and then a barely resisted seduction becomes in the wife’s telling a brutal attack and its cruel aftermath: If de Carrouges loses the duel, Marguerite stands to be burned at the stake for lying.

Directed by Ridley Scott with panoply and muscle (and a generous helping of Hundred Years War battlefield gore), “The Last Duel” works as both an entertainment – a bottle-blond Affleck roisters happily and hammily along the edges as le Gris’ noble sponsor -- and a cautionary tale of how far we’ve come and how far we haven’t. With a coolly modern gaze, it demolishes myths of knightly valor, courtly love, and the male narratives that surround sexual assault. Damon has what is for him a character part; possibly he and Affleck intend this movie as an exhibit for the defense in the court of #MeToo-era public opinion, but the actor burrows down into de Carrouges’s bull-like stolidity and naivete. (It’s just a shame about the mullet.) The key to the movie, though, is Comer, who became famous as a jaunty psychopath on AMC’s “Killing Eve” and who here plays a woman made tragically aware of how constricted life is for even the literate, high-born wife of a knight — of how Marguerite is not seen, never heard, but merely owned. (The only witness to her version of events is us.) In Comer’s subtly measured performance, what could be a didactic fable becomes flesh.

If you enjoyed this edition of Ty Burr’s Watch List, please feel free to share it with friends.

If you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to sign up for additional reviews and to join discussions, here’s how:

If you’re already a paying subscriber, I thank you for your support.