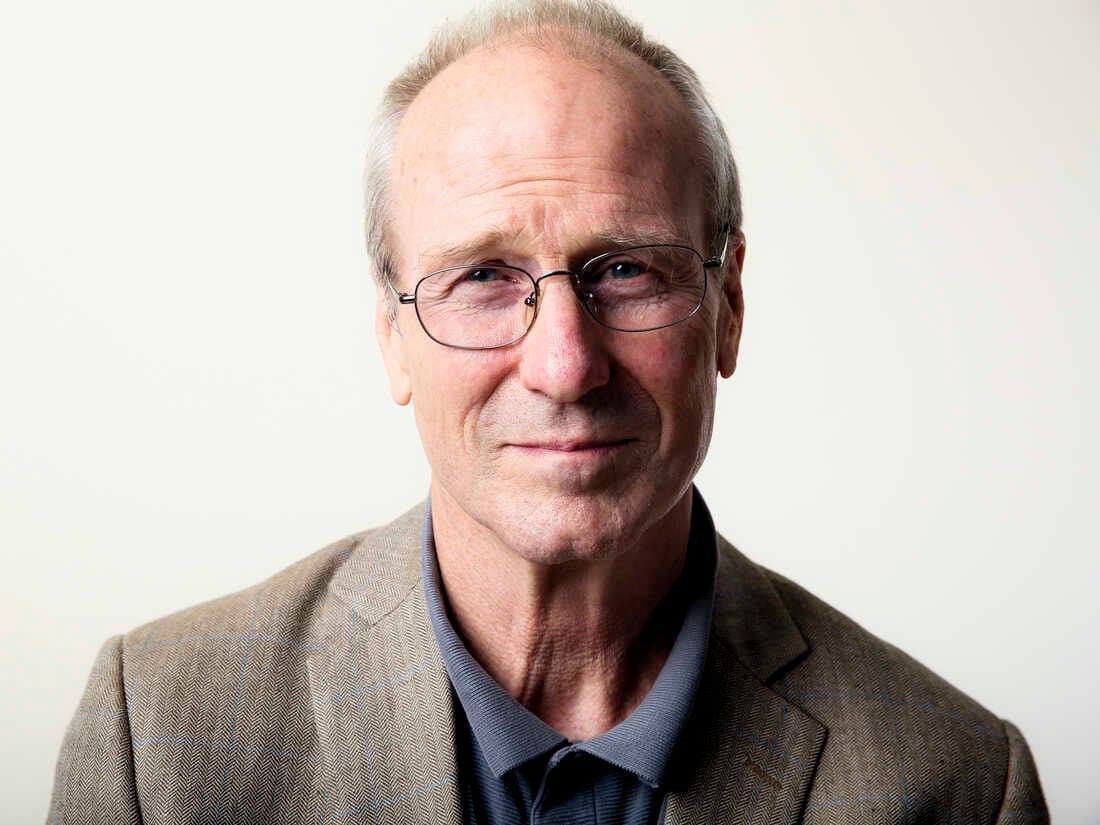

William Hurt 1950-2022

Thoughts on an actor who moved to his own private tune.

William Hurt always seemed slightly stunned by movie stardom. It annoyed him – you could see it in the narrowing of his eyes. Stardom was for people who knew what they wanted, and in his onscreen performances and offscreen interviews, Hurt was for better and for worse a seeker. The quest was the goal, and wherever it led was less important than what you learned as you went. He was one of those stars – Harrison Ford is another, as was Peter O’Toole – whose matinee idol good looks were a botheration, a distraction from the business at hand. Other people’s hang-up, and when the other people include the entire Hollywood power structure and the moviegoing masses, the response can be grumpiness (Ford) or debauchery (O’Toole) or the cynicism of the quick payday (De Niro and Pacino). With Hurt, fame just seemed to fuel a weariness, a greater hesitancy in those measured cadences of his speech.

Also: He was weird in a way most movie stars aren’t, and in a way often difficult for viewers and the culture to pigeonhole. This is what made Hurt fascinating to watch while contributing to an air of unpredictability, of diffidence sliding into danger, both onscreen and off. It’s why his Tom Grunick, the ambitious TV journalist of “Broadcast News” (1987), is simultaneously attractive and repellent, a hollow man who can cry on cue and who represents the future of on-air media. It’s what makes his mind-melting, body-morphing research scientist in “Altered States” (1980) such a mercurial debut. And that spaciness combined with a hint of violence simmering in the background (and who knows when it might come) underscores Marlee Matlin’s stories of her relationship with Hurt in the mid-1980s: The drug use, the physical abuse, the mind games. Being around him wasn’t often easy. One senses that being him wasn’t always a picnic either.

It’s interesting what one’s mind first flashes on when a famous person dies. As news of Hurt’s passing hit social media Sunday – he was 71 and had been fighting prostate cancer since 2018 – some immediately “saw” him in “Broadcast News,” while others thought of Molina, the gay prisoner and tale-spinner of “Kiss of the Spider Woman” (1985), the movie that won the actor his Oscar. For many people under the age of 35, he was General Ross in the “Avengers” movies; for many people over 35, it’s him and Kathleen Turner steaming the sheets in “Body Heat” (1981). Me, I went to the scene in “The Big Chill” (1983) where Hurt’s Nick interviews himself on a living room sofa, play-acting both an interlocutor and his squirming subject for a video camera. It’s a delicious bit, the character admitting his pain while tap-dancing around it in denial, and there’s a sneaking sense that Hurt is interrogating himself as an actor, holding his own feet to the fire to see what’s pretense and what’s truth. Truth seemed to matter a lot to him, and he seemed willing to go pretty far out there to find it.

Sunday night, stories and apocrypha circulated online. Someone re-upped on Twitter a long, marvelous thread about Hurt attending a Chicago stage production of Clifford Odets’ “Golden Boy” – the only person in the audience that night, he stood and clapped and wept and hung out with the cast until the wee hours, overwhelmed by his own emotions and grateful to have his faith in theater renewed. I was reminded, too, of this passage from a particularly salty interview with Kathleen Turner from a few years back:

I read in your memoir that William Hurt was into magic mushrooms. Did he ever try and get you to take them with him?

No, I never tried any of those things that he liked. Bill can be very odd.

How so?

I remember one night while we were shooting “Body Heat” we were sitting around, and for some reason he wanted to talk about how we’d each like to die. I don’t remember what my answer was, but he said he wanted to be sucked up into a jet engine. You would find yourself in that kind of discussion with Bill. Then when we did “The Accidental Tourist,” Bill was sober, so there were fewer discussions like that. God, you did not want to get Bill talking too much.

Anecdotes like this are why I feel like Hurt’s movies were just the tip of a much larger iceberg that existed offscreen – that in some sense we never saw the full measure of what he could do. (I didn’t have the privilege of seeing him onstage, and it’s probable there was more to the iceberg there.) His reserve – that cerebral drawl of his, as if here were telling you only half of what he was thinking – drew audiences in but was, in the end, impenetrable. Is that why major stardom faded after the acclaim and awards of the 1980s? Hurt never stopped working and he was always welcome company no matter how small the part, but his run as an above-the-title lead was comparatively short. Did audiences and producers walk away from him – or did he walk away from us?

The major credits in the filmography are easily rented online: “Altered States,” “Body Heat,” “The Big Chill,” “Broadcast News,” “Children of a Lesser God” (1986), “The Accidental Tourist” (1988). The exception is “Kiss of the Spider Woman,” which is unavailable as a VOD rental but which can be found on YouTube (for now) in a decent bootleg print. It’s also worth seeking out Wayne Wang’s “Smoke” (1995), a moody shaggy dog tale set in Brooklyn, with a script by Paul Auster, and especially “The Doctor” (1991), in which the title character played by Hurt is a coldly efficient medical professional whose own cancer diagnosis affects his bedside manner for the better. That last one, in which a man awakens to compassion by degrees, may be the great William Hurt movie that got away. RIP.

If you enjoyed this edition of Ty Burr’s Watch List, please feel free to share it with friends.

If you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to sign up for additional postings and to join the discussions, here’s how:

If you’re already a paying subscriber, I thank you for your generous support.